Hollywood Magazine (1942) - Hollywood Oversight

Details

- article: Hollywood Oversight

- journal: Hollywood Magazine (November 1942)

- issue: volume 31, issue 11, pages 62-63

- journal ISSN:

- publisher: Fawcett Publications, Inc.

- keywords: Alfred Hitchcock, New York City, New York, Norman Lloyd, Saboteur (1942), Universal Studios

Links

Article

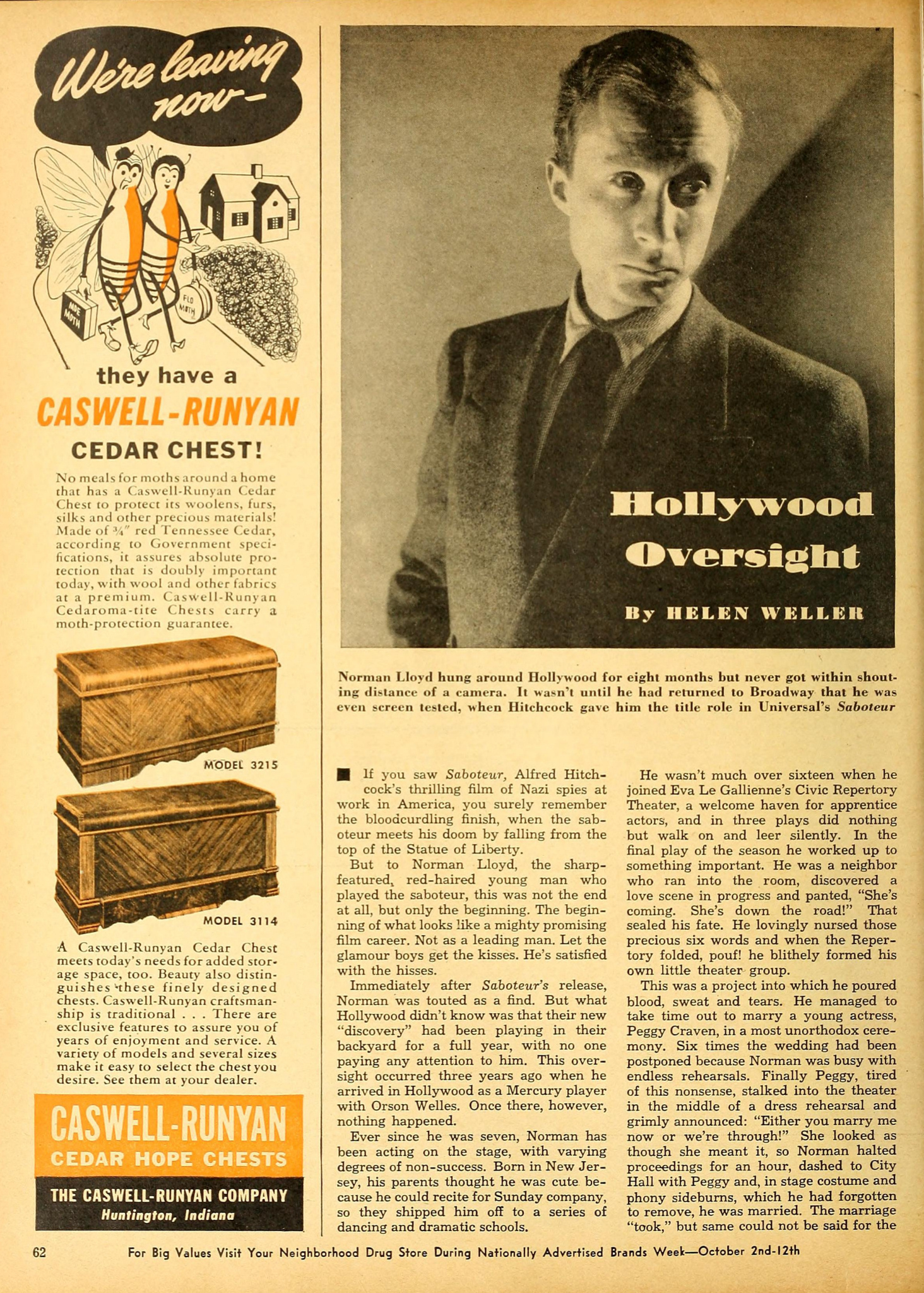

Norman Lloyd hung around Hollywood for eight months but never got within shouting distance of a camera. It wasn't until he had returned to Broadway that he was even screen tested, when Hitchcock gave him the title role in Universal's Saboteur

If you saw Saboteur, Alfred Hitchcock's thrilling film of Nazi spies at work in America, you surely remember the bloodcurdling finish, when the saboteur meets his doom by falling from the top of the Statue of Liberty.

But to Norman Lloyd, the sharp-featured, red-haired young man who played the saboteur, this was not the end at all, but only the beginning. The beginning of what looks like a mighty promising film career. Not as a leading man. Let the glamour boys get the kisses. He's satisfied with the hisses.

Immediately after Saboteur's release, Norman was touted as a find. But what Hollywood didn't know was that their new "discovery" had been playing in their backyard for a full year, with no one paying any attention to him. This oversight occurred three years ago when he arrived in Hollywood as a Mercury player with Orson Welles. Once there, however, nothing happened.

Ever since he was seven, Norman has been acting on the stage, with varying degrees of non-success. Born in New Jersey, his parents thought he was cute because he could recite for Sunday company, so they shipped him off to a series of dancing and dramatic schools.

He wasn't much over sixteen when he joined Eva Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory Theater, a welcome haven for apprentice actors, and in three plays did nothing but walk on and leer silently. In the final play of the season he worked up to something important. He was a neighbor who ran into the room, discovered a love scene in progress and panted, "She's coming. She's down the road!" That sealed his fate. He lovingly nursed those precious six words and when the Repertory folded, pouf! he blithely formed his own little theater group.

This was a project into which he poured blood, sweat and tears. He managed to take time out to marry a young actress, Peggy Craven, in a most unorthodox ceremony. Six times the wedding had been postponed because Norman was busy with endless rehearsals. Finally Peggy, tired of this nonsense, stalked into the theater in the middle of a dress rehearsal and grimly announced: "Either you marry me now or we're through!" She looked as though she meant it, so Norman halted proceedings for an hour, dashed to City Hall with Peggy and, in stage costume and phony sideburns, which he had forgotten to remove, he was married. The marriage "took," but same could not be said for the theater group which disbanded from lack of public enthusiasm.

With a wife to support, Norman couldn't afford to dilly-dally. He made quick tracks to Orson Welles, then a young director with screwball ideas, who was collecting earnest and starving young actors for his Mercury Theater Group. He played several seasons with him, and when Welles received the Hollywood call, Norman and the rest of the group went too, on short term contracts.

Norman was to have had a nice fat part in Heart of Darkness, only it was never made. Instead he played tennis while Welles discarded one script after another. When he finally decided on Citizen Kane, there wasn't any role for Norman, so he packed up and went back East without even sighting a movie camera.

In New York things took a nose dive. Play after play in which he appeared petered out a few hours after opening. Life became a series of rehearsals and closings—and making excuses to the landlord. A baby had arrived, and Norman decided that the time had come to sever all relations with acting and look for a real job. But first, hoping to get his hands on some quick cash, he brought a play he had written to an agent. The agent agreed to look at it, then suddenly exclaimed, "Say, Alfred Hitchcock is in town and he's looking for a fellow of your description for Saboteur. I'll make an appointment for you." The date was set for that very afternoon, as Hitchcock was leaving for Hollywood the next morning.

"It was more like a social get-together," says Norman. "We discussed pictures, plays and books. He said nothing at all about the role and I thought I didn't stand a chance. Then casually he said, "I'm going to test you. Get some material and come back." I dug up a script of Blind Alley, and within half an hour I was before the cameras for the first time. When Hitchcock did leave, he had my test with him, and the day after his arrival in Hollywood he wired me to come out in a hurry.

"Peggy and I were so afraid that it was going to be a repetition of my first Hollywood trip that she wouldn't go with me. She said, 'You go alone. I'll stay home and keep my finders crossed.' I told this to Hitchcock. The day after the picture was shown he said to me, 'Well, you may as well go back and get your wife and baby.' That was the best compliment of all."

Now Norman Lloyd's a film actor with a shining movie future. A large home? Nursemaid for the baby? Expensive suits and vacations in Sun Valley? Well, not exactly. The years of public indifference and the parade of flops have made him and Peggy cautious.

Even his friends, accustomed to linking his name with bad luck, thought it was another fellow who got the break in Saboteur. One of them, in fact, called Mrs. Lloyd right after he had seen an item in the papers about Saboteur with Norman mentioned in the title role. "Isn't it too bad about Norman," he said. "First he's out of work—and now somebody else is using his name."

That's Norman's favorite story. With things looking up, he can afford to laugh at it.