The MacGuffin: News and Comment (04/Aug/2012)

(c) Ken Mogg (2012)

Aug 4

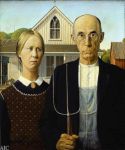

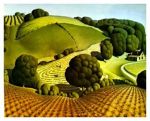

I trust that my regular readers have by now examined - and very possibly bought - the revised edition of Michael Gould's 'Surrealism and the Cinema' (1976; 2011), which was mentioned here on April 14 and is available for download. Gould has a sound appreciation of painting in general and the work of the Surrealists (inspired by Dadaist and Symbolist principles) in particular. I like how he notes that paintings by Edward Hopper and Grant Wood are related to such Hitchcock films as Psycho and The Birds. (See the illustrations of Wood's 'American Gothic' and 'Young Corn' below.) But as this week has seen Hitchcock's Vertigo voted by international critics the greatest film ever made, I want to talk about that film and in particular the scene in the redwood forest where 'Madeleine' (Kim Novak) points to the rings in a cross-section of a felled tree. 'Here I was born and here I died [she says]. It was only a moment for you. You took no notice.' Gould's description of the forest scene is not quite accurate, for he only approximates what Madeleine says. He claims she says, 'That is where I came from', which removes most of the line's nuance. However, he continues: 'Intriguingly, as [Madeleine] pinpoints a moment in time she is, by omission, raising the issue of death.' This is in keeping with Gould's suggestion earlier that Vertigo is metaphorically about 'the simultaneous fear of and attraction to death', and that Judy/Madeleine's 'fear of returning to the church [is] ... a fear of being totally subsumed by her Madeleine persona' (rather than simply a fear of being revealed as an accomplice in a crime). What struck me about that formulation in relation to the forest scene is how Gould's avoiding of an important nuance typifies how critics in general (I've noticed) appear to avoid facing the 'meaning' of what Madeleine says there - which is very like Judy's own avoidance of her fear of 'being totally subsumed'. For consider this. If you care (dare?) to ask yourself whom Judy/Madeleine is addressing in the forest when she says 'It was only a moment for you', there is only one possible ultimate answer - distasteful as it may be to a lot of critics (apparently)! As I wrote long ago: Madeleine/Judy is here apostrophising God himself (and the total submission to something/someone greater than oneself such a notion implies)! But if you can't stand to acknowledge those implications (and the strong Catholic iconography on show in Vertigo, although not without ambiguity - as I have also often noted), then you may simply not take in the daringness of the scene. (Ironically, Gould emphasises in his book the audacity of Surrealist modes and methods.) I'll try to be clear. Judy/Madeleine is not principally addressing Scottie (James Stewart) who is standing alongside her, or an ancestor, the husband of Carlotta, in her past, or even the felled tree itself - though the latter is the most likely, and plausible, candidate for her address apart from 'God', as Hitchcock would have been well aware. In a film filled with a score of references to paintings, films, and works of theatre and literature (see "The Fragments of the Mirror" on this site), it's very likely that Hitchcock had in mind apropos the redwood forest scene the lyrics of the recent hit Broadway musical, 'Paint Your Wagon' (1951-52), in which a character sings, 'I talk to the trees/ But they don't listen to me.' That would have been perfectly in keeping with his method of ambiguous reference which he had long used in his many-levelled films, as something that would help make those films acceptable to diverse audiences and points of view. (Similarly, he knew that he had to literally spell out at the start of the 1956 The Man Who Knew Too Much the word 'cymbals', lest some audiences wouldn't know what was being referenced and might later get confused by the homophone with 'symbols' and be distracted or put off.) Of course, Vertigo also works (like the voyeuristic Rear Window) as an analogue of cinema itself (cinema-making, cinema-viewing), a situation in which the director and the spectator both up to a point are placed in a God-like position. That explains part of the force of the climactic line in Hitchcock's 'Rope where Rupert (James Stewart) finally rounds on his two protégés and asks, 'Did you think you were God?' But Hitchcock knew that neither he nor anyone else was God. Vertigo is both a humbling film and yet boldly (audaciously) is about the possibility of a 'transcendent' (superior) view of how things are. In that, too, as Gould can remind us (see his Introduction), Vertigo has a surreal tendency.

This material is copyright of Ken Mogg and the Hitchcock Scholars/'MacGuffin' website (home page) and is archived with the permission of the copyright holder. |