National Film Theatre: Fifty Famous Films (1915-1945) - Blackmail

Details

- book chapter: Blackmail

- author(s):

- appears in: Creating National Film Theatre: Fifty Famous Films (1915-1945) (pages 58-59)

- keywords: Alfred Hitchcock, Alice White, Anny Ondra, Benn W. Levy, Blackmail (1929), British International Pictures, C. Wilfred Arnold, Charles Bennett, Charles Paton, Cyril Ritchard, Donald Calthrop, Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, Henry Stafford, Hubert Bath, Joan Barry, John Longden, John Maxwell, Phyllis Monkman, Sara Allgood, Scotland Yard, London

Links

Chapter

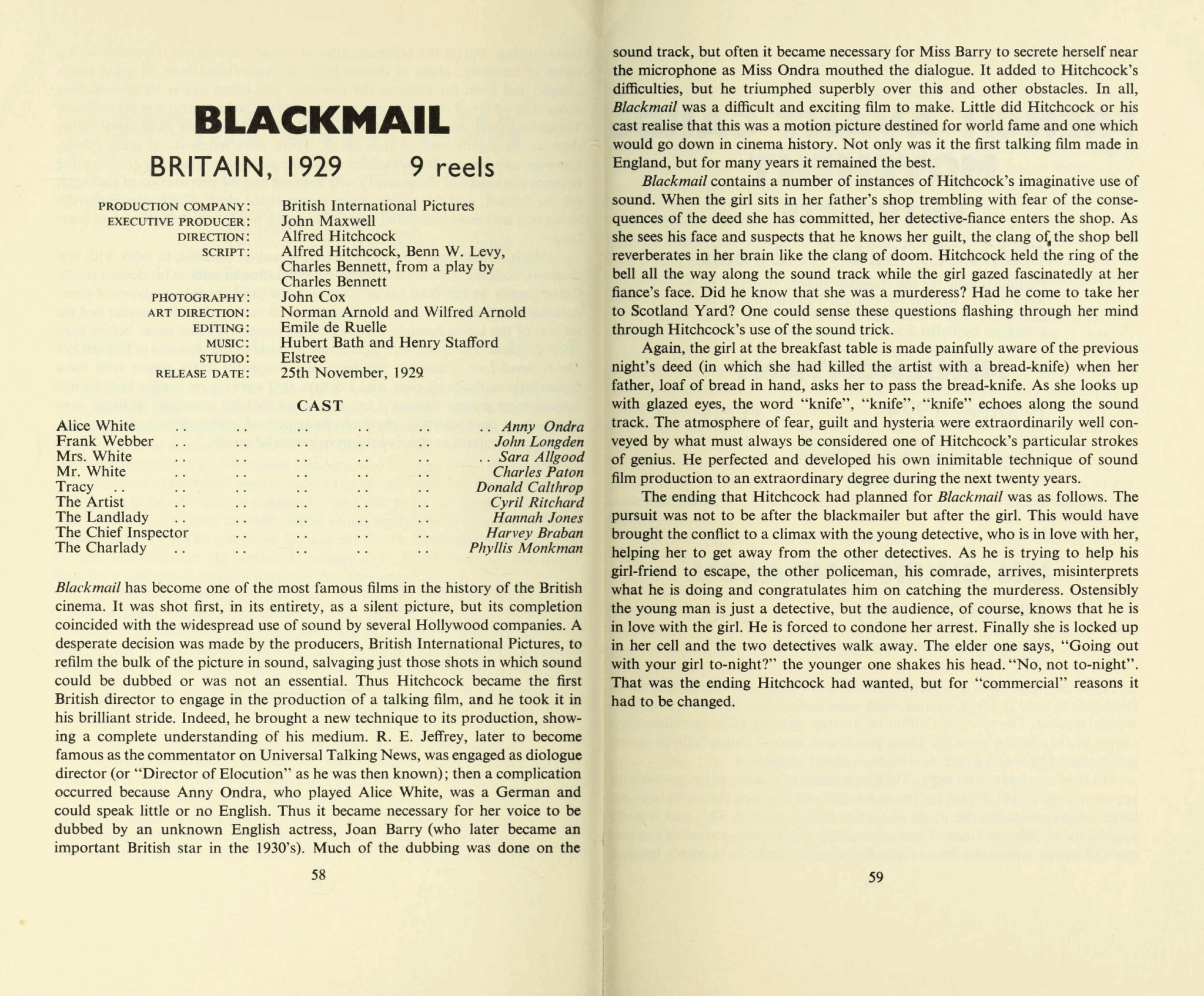

BLACKMAIL

BRITAIN, 1929, 9 reels

- Production Company : British International Pictures

- Executive Producer : John Maxwell

- Direction : Alfred Hitchcock

- Script : Alfred Hitchcock, Benn W. Levy, Charles Bennett, from a play by Charles Bennett

- Photography : John Cox

- Art Direction : Norman Arnold and Wilfred Arnold

- Editing : Emile de Ruelle

- Music : Hubert Bath and Henry Stafford

- Studio : Elstree

- Release Date : 25th November, 1929

CAST

- Alice White : Anny Ondra

- Frank Webber : John Longden

- Mrs. White : Sara Allgood

- Mr. White : Charles Paton

- Tracy : Donald Calthrop

- The Artist : Cyril Ritchard

- The Landlady : Hannah Jones

- The Chief Inspector : Harvey Braban

- The Charlady : Phyllis Monkman

Blackmail has become one of the most famous films in the history of the British cinema. It was shot first, in its entirety, as a silent picture, but its completion coincided with the widespread use of sound by several Hollywood companies. A desperate decision was made by the producers, British International Pictures, to refilm the bulk of the picture in sound, salvaging just those shots in which sound could be dubbed or was not an essential. Thus Hitchcock became the first British director to engage in the production of a talking film, and he took it in his brilliant stride. Indeed, he brought a new technique to its production, showing a complete understanding of his medium. R. E. Jeffrey, later to become famous as the commentator on Universal Talking News, was engaged as dialogue director (or "Director of Elocution" as he was then known); then a complication occurred because Anny Ondra, who played Alice White, was a German and could speak little or no English. Thus it became necessary for her voice to be dubbed by an unknown English actress, Joan Barry (who later became an important British star in the 1930's). Much of the dubbing was done on the sound track, but often it became necessary for Miss Barry to secrete herself near the microphone as Miss Ondra mouthed the dialogue. It added to Hitchcock's difficulties, but he triumphed superbly over this and other obstacles. In all, Blackmail was a difficult and exciting film to make. Little did Hitchcock or his cast realise that this was a motion picture destined for world fame and one which would go down in cinema history. Not only was it the first talking film made in England, but for many years it remained the best.

Blackmail contains a number of instances of Hitchcock's imaginative use of sound. When the girl sits in her father's shop trembling with fear of the consequences of the deed she has committed, her detective-fiancé enters the shop. As she sees his face and suspects that he knows her guilt, the clang of the shop bell reverberates in her brain like the clang of doom. Hitchcock held the ring of the bell all the way along the sound track while the girl gazed fascinatedly at her fiancé's face. Did he know that she was a murderess? Had he come to take her to Scotland Yard? One could sense these questions flashing through her mind through Hitchcock's use of the sound trick.

Again, the girl at the breakfast table is made painfully aware of the previous night's deed (in which she had killed the artist with a bread-knife) when her father, loaf of bread in hand, asks her to pass the bread-knife. As she looks up with glazed eyes, the word "knife", "knife", "knife" echoes along the sound track. The atmosphere of fear, guilt and hysteria were extraordinarily well conveyed by what must always be considered one of Hitchcock's particular strokes of genius. He perfected and developed his own inimitable technique of sound film production to an extraordinary degree during the next twenty years.

The ending that Hitchcock had planned for Blackmail was as follows. The pursuit was not to be after the blackmailer but after the girl. This would have brought the conflict to a climax with the young detective, who is in love with her, helping her to get away from the other detectives. As he is trying to help his girl-friend to escape, the other policeman, his comrade, arrives, misinterprets what he is doing and congratulates him on catching the murderess. Ostensibly the young man is just a detective, but the audience, of course, knows that he is in love with the girl. He is forced to condone her arrest. Finally she is locked up in her cell and the two detectives walk away. The elder one says, "Going out with your girl to-night?" the younger one shakes his head. "No, not to-night". That was the ending Hitchcock had wanted, but for "commercial" reasons it had to be changed.