Los Angeles Times (05/Jan/1941) - He Makes the Movies Move

Details

- article: He Makes the Movies Move

- author(s): Lupton A. Wilkinson

- newspaper: Los Angeles Times (05/Jan/1941)

- keywords: Alfred Hitchcock, Alma Reville, Before the Fact (1932) by Francis Iles, Foreign Correspondent (1940), Hitchcock Chronology: 1938, Joan Harrison, Joel McCrea, London, England, New York City, New York, Rebecca (1940), Sabotage (1936), Suspicion (1941), Sylvia Sidney, The 39 Steps (1935), The Lady Vanishes (1938), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), Walter Wanger, Young and Innocent (1937)

Article

He Makes the Movies Move

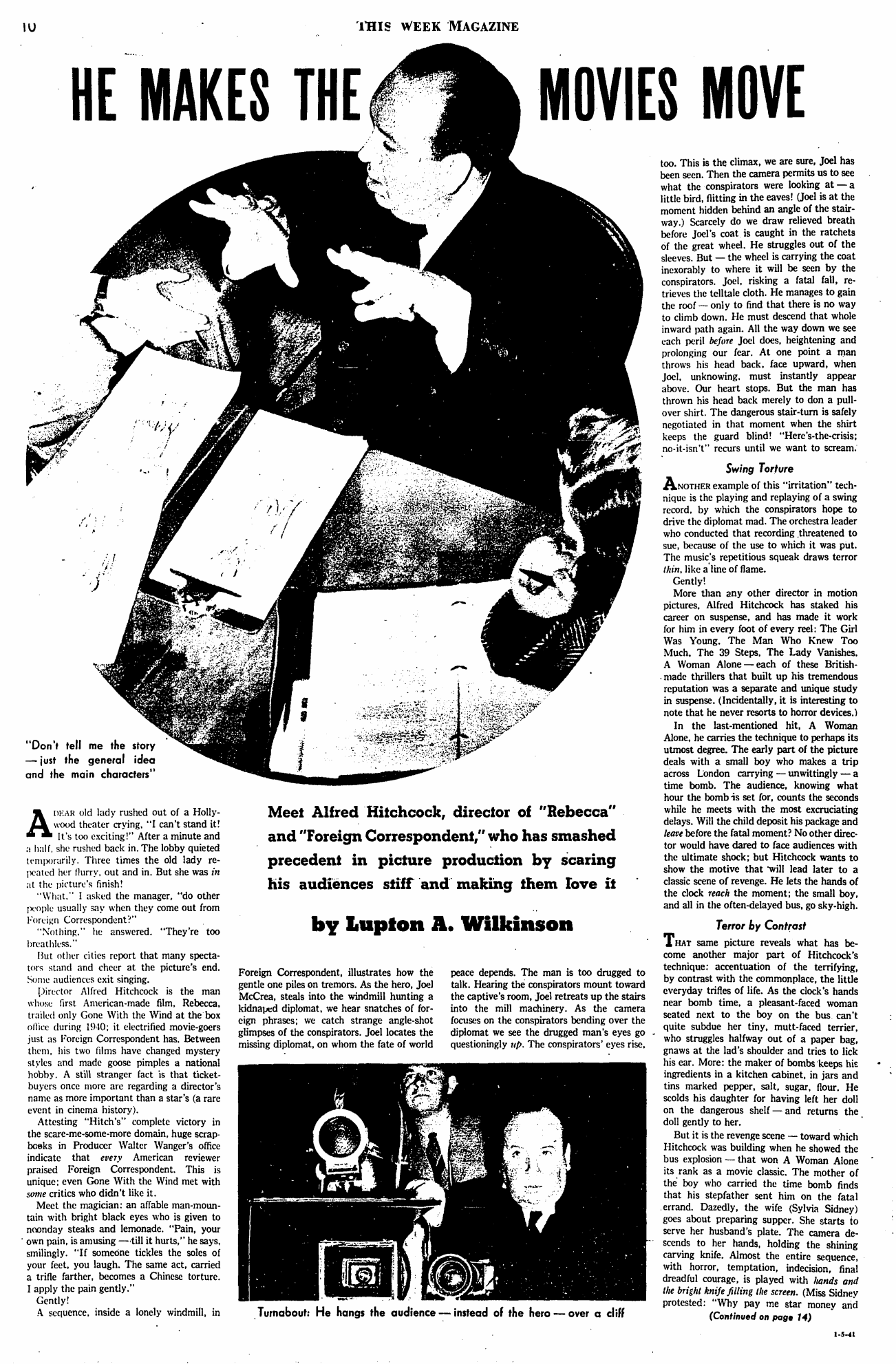

Meet Alfred Hitchcock, director of "Rebecca" and "Foreign Correspondent," who has smashed precedent in picture production by scaring his audiences stiff and making them love it

A dear old lady rushed out of a Hollywood theater crying, "I can't stand it! It's too exciting!" After a minute and a half, she rushed back in. The lobby quieted temporarily. Three times the old lady repeated her flurry, out and in. But she was in at the picture's finish!

"What," I asked the manager, "do other people usually say when they come out from Foreign Correspondent?"

"Nothing." he answered. "They're too breathless."

But other cities report that many spectators stand and cheer at the picture's end. Some audiences exit singing.

Director Alfred Hitchcock is the man whose first American-made film, Rebecca, trailed only Gone With the Wind at the box office during 1940; it electrified movie-goers just as Foreign Correspondent has. Between them, his two films have changed mystery styles and made goose pimples a national hobby. A still stranger fact is that ticket-buyers once more arc regarding a director's name as more important than a star's (a rare event in cinema history).

Attesting "Hitch's" complete victory in the scare-me-some-more domain, huge scrap-books in Producer Walter Wanger's office indicate that every American reviewer praised Foreign Correspondent. This is unique; even Gone With the Wind met with some critics who didn't like it.

Meet the magician: an affable man-mountain with bright black eyes who is given to noonday steaks and lemonade. "Pain, your own pain, is amusing — till it hurts," he says, smilingly. "If someone tickles the soles of your feet, you laugh. The same act, carried a trifle farther, becomes a Chinese torture. I apply the pain gently."

Gently!

A sequence, inside a lonely windmill, in Foreign Correspondent, illustrates how the gentle one piles on tremors. As the hero, Joel McCrea, steals into the windmill hunting a kidnapped diplomat, we hear snatches of foreign phrases; we catch strange angle-shot glimpses of the conspirators. Joel locates the missing diplomat, on whom the fate of world peace depends. The man is too drugged to talk. Hearing the conspirators mount toward the captive's room, Joel retreats up the stairs into the mill machinery. As the camera focuses on the conspirators bending over the diplomat we see the drugged man's eyes go questioningly up. The conspirators' eyes rise, too. This is the climax, we are sure, Joel has been seen. Then the camera permits us to see what the conspirators were looking at a little bird, flitting in the eaves! (Joel is at the moment hidden behind an angle of the stairway.) Scarcely do we draw relieved breath before Joel's coat is caught in the ratchets of the great wheel. He struggles out of the sleeves. But — the wheel is carrying the coat inexorably to where it will be seen by the conspirators. Joel, risking a fatal fall, retrieves the tell-tale cloth. He manages to gain the roof — only to find that there is no way to climb down. He must descend that whole inward path again. All the way down we see each peril before Joel docs, heightening and prolonging our fear. At one point a man throws his head back, face upward, when Joel, unknowing, must instantly appear above. Our heart stops. But the man has thrown his head back merely to don a pullover shirt. The dangerous stair-turn is safely negotiated in that moment when the shirt keeps the guard blind! "Here's-the-crisis; no-it-isn't" recurs until we want to scream.

Swing Torture

Another example of this "irritation" technique is the playing and replaying of a swing record, by which the conspirators hope to drive the diplomat mad. The orchestra leader who conducted that recording threatened to sue, because of the use to which it was put. The music's repetitious squeak draws terror thin, like a line of flame.

Gently!

More than any other director in motion pictures, Alfred Hitchcock has staked his career on suspense, and has made it work for him in every foot of every reel: The Girl Was Young, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes, A Woman Alone — each of these British-made thrillers that built up his tremendous reputation was a separate and unique study in suspense. (Incidentally, it is interesting to note that he never resorts to horror devices.)

In the last-mentioned hit, A Woman Alone, he carries the technique to perhaps its utmost degree. The early part of the picture deals with a small boy who makes a trip across London carrying — unwittingly a time bomb. The audience, knowing what hour the bomb-is set for, counts the seconds while he meets with the most excruciating delays. Will the child deposit his package and leave before the fatal moment? No other director would have dared to face audiences with the ultimate shock; but Hitchcock wants to show the motive that 'Will lead later to a classic scene of revenge. He lets the hands of the clock reach the moment; the small boy, and all in the often-delayed bus, go sky-high.

Terror by Contrast

That same picture reveals what has become another major part of Hitchcock's technique: accentuation of the terrifying, by contrast with the commonplace, the little everyday trifles of life. As the clock's hands near bomb time, a pleasant-faced woman seated next to the boy on the bus can't quite subdue her tiny, mutt-faced terrier, who struggles halfway out of a paper bag, gnaws at the lad's shoulder and tries to lick his ear. More: the maker of bombs keeps his ingredients in a kitchen cabinet, in jars and tins marked pepper, salt, sugar, flour. He scolds his daughter for having left her doll on the dangerous shelf — and returns the doll gently to her.

But it is the revenge scene — toward which Hitchcock was building when he showed the bus explosion — that won A Woman Alone its rank as a movie classic. The mother of the boy who carried the time bomb finds that his stepfather sent him on the fatal errand. Dazedly, the wife (Sylvia Sidney) goes about preparing supper. She starts to serve her husband's plate. The camera descends to her hands, holding the shining carving knife. Almost the entire sequence, with horror, temptation, indecision, final dreadful courage, is played with hands and the bright knife filling tile screen. (Miss Sidney protested: "Why pay me star money and never let the audience see me in my big scene?" She was wrong; the film added much to her dramatic fame.)

The Lady Vanishes, which won the 1938 award of the New York movie critics as the best-directed picture of that year, is another example of the Hitchcock method at its best. Incidentally, it betrays one of Hitch's idiosyncrasies: the action centers mainly on a train. In most Hitchcock pictures you will find trains, buses (by the dozen), ships and planes. This is part of the man. (His pictures are highly personal; he is the No. 1 writer as well as the director.) Ever since he can remember, Hitch has been obsessed with a love for travel. Hitch was the son of a fruit importer in London; the bright and varied goods in the shop set him longing for far places. By the time he reached his eighth birthday, he had ridden to the end of every bus line — which amounted to almost a life career in London. Those terminals included the London docks, accelerating his dreams. For a hobby he kept a huge wall map of the world. Each afternoon he asked a newsdealer to let him see Lloyd's bulletin; then he hurried home to mark with flagpins the positions of British ships throughout the world.

Made Good Fast

That same newsdealer let him read motion-picture trade papers. After studying — not very long — engineering and art, he talked himself into a film job. Love of the work and application (he was strictly reared, didn't have a date with a girl till he was independent — then he was too busy) pushed him up fast. On his first directorial job he combined his old love of travel with his movie making; he took a film company pretty much all over Europe on a $50,000 total budget. That company included a hazel-eyed girl named Alma Reville, who became his co-writer and general assistant. During the ninth shooting tour two things happened. His employers cabled, "Come home; use sets," which ended his travels for a while. But, just before that he had had a talk with his assistant. "Look here, Miss Reville, we're together a lot. I think we're awfully fond of each other, don't you? I mean, what do you say — ?"

Mrs. Hitchcock admits she thought it was about time! Theirs has been a happy, congenial marriage. Twelve-year-old Patricia, their daughter, is their favorite critic. If she seems surprised by a scene, Hitch is likely to think it's good. For Sunday recreation the family goes plane-riding.

When the producer Walter Wanger employed Hitchcock to direct Foreign Correspondent, Hitch said: "Don't tell us the story — just the general idea and the principal characters." Wanger complied. Hitch recalls: "We — Miss Joan Harrison and I — decided at once we would have terrible people and events menace this American newspaperman — worse than any gangster practices at home. Where would we start the story? We closed our eyes and let our minds travel: Italy, France, Belgium, Holland. Suddenly I saw a windmill. Ah! I'd let the hero see a windmill with its wheel turning against the wind." From that eerie start, working backward and forward, Hitch and his associates evolved the Foreign Correspondent script that reached the screen. No wonder Hitchcock pictures move!

The man's' creative imagination is already hot-wrapped in his next movie thriller, Before the Fact. It's drawn from a published novel, but Hitch's mind is doing things to it. A relined, innocent girl marries a shoddy-souled adventurer. At first the man is just a petty sharper. We see his craving for money and an easy life lead him to more and more serious crime — until he assists in the murder of his wife's father. We see the slow, groping growth of his wife's reluctant understanding of what she has married. We watch the man's power over her increase almost to hypnotism, so that she cannot tear herself loose. This, with all the Hitchcock suspense techniques, mounts to a fearful climax, where the husband asks his ill wife to do a simple thing — drink a glass of milk. (No fair telling the ending.)

I said, "You'll play the characters straight in this one, of course."

Good humor shook my host. "Not at all. We'll play it very gaily, on the surface, a marital comedy." He smiled his gentlest smile: "Just a comedy, in which murder creeps underneath."

Creeps! More likely gallops!

In the old days, suspense in the movies reached its high in The Perils of Pauline, where the heroine was left hanging over the cliff at the end of each instalment. Hitchcock hangs the audience over the cliff throughout each picture — a lifetime of cliff-hanging in two hours!