Hollywood Magazine (1942) - Hitchcock Keeps 'Em Guessing

Details

- article: Hitchcock Keeps 'Em Guessing

- journal: Hollywood Magazine (April 1942)

- issue: volume 31, issue 4, pages 22-23

- journal ISSN:

- publisher: Fawcett Publications, Inc.

- keywords: Alan Baxter, Alfred Hitchcock, New York City, New York, Norman Lloyd, Priscilla Lane, Saboteur (1942), Universal Studios

Links

Article

"We've been sabotaged!" Angrily Director Alfred Hitchcock made the accusation.

His assistant, Fred Frank, had called to report he had the necessary dust storm for the new Hitchcock picture, Saboteur. Three tons of dust.

"Good," said Hitchcock. "We ought to be able to brew up quite a tidy mess with that. How about the bearded lady?"

"All set with Hairy Helen," said Frank. "Likewise okay on the waterfall, human skeleton, Siamese twins and one dozen midgets."

"Good," said Hitchcock. "And the fat lady?"

Frank groaned. "No fat lady," he confessed. "Dad-blast this diet-conscious town of Hollywood! Try as I have, I haven't found a single dame who will admit she tips the scales at more than a dainty 137 and you said nothing under 350 pounds would do."

Hitchcock stared unbelievingly at his assistant. "No fat lady?" he muttered. We've been sabotaged!"

Eventually the day was saved. Someone remembered the C. F. Zeiger show was wintering in Phoenix, Ariz., and Marie LeDeaux, a sprightly lass standing a' bare five feet tall and weighing a generous 375 pounds was imported to play the colorful role in the picture's circus freak sequence. No one doubted, however, that had an impasse been reached, Hitchcock would have donned a wig and skirts and loaned his own 295 pounds for the good of the cause. It was a golden opportunity for one of those bits in which, for good luck, he always injects himself in his pictures.

In lieu of the fat lady bit, Hitchcock whipped up a novel few moments which ought to give the Hays Office something to ponder. He plays a deaf mute who makes a play for a passing blonde via the sign language and gets his face slapped for the conversation piece. Or maybe the Hays Office employs a sign language censor and Hitchcock will land on the cutting room floor.

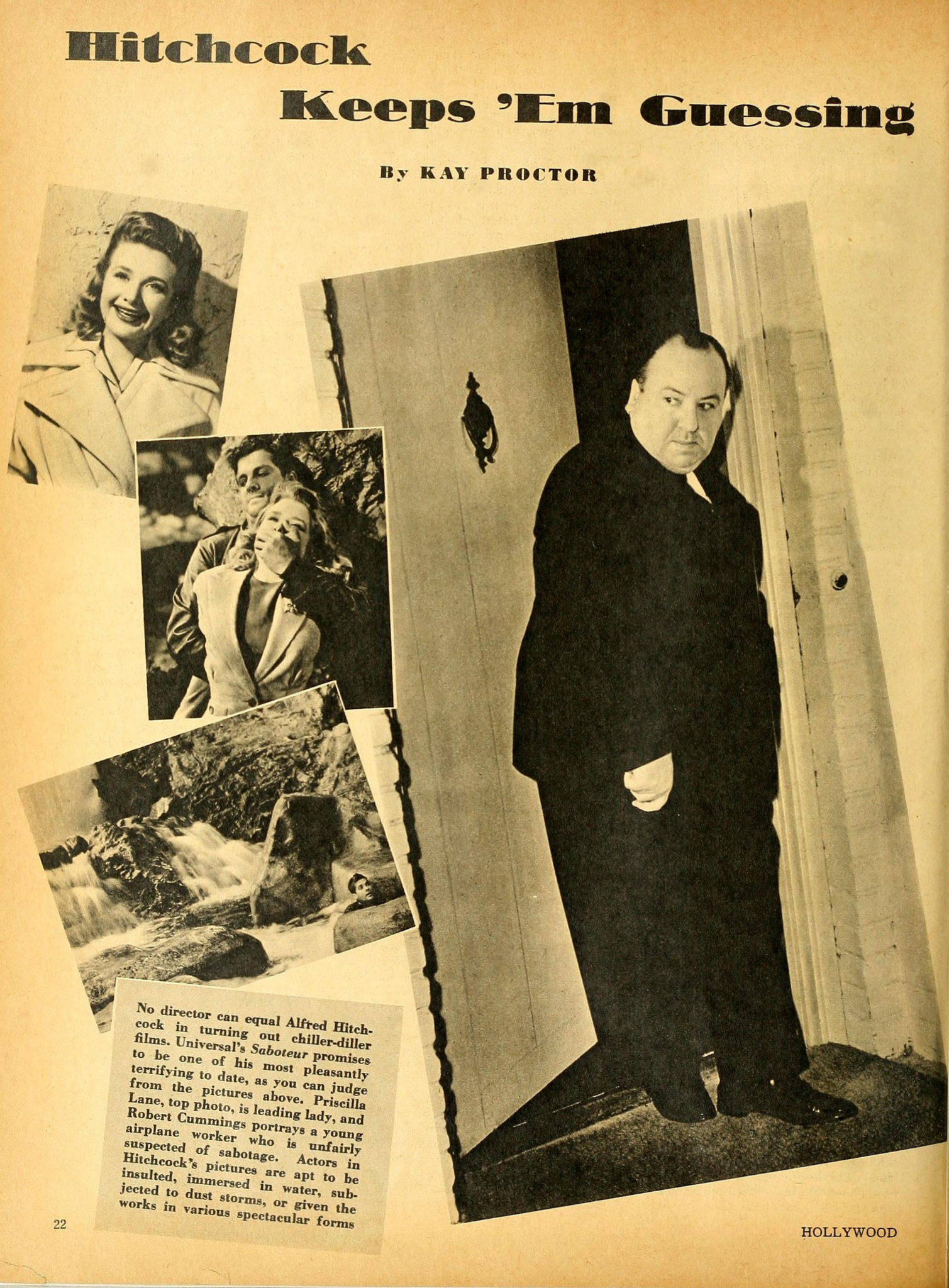

Saboteur, Universal's answer to the cry for timely pictures, is one of those suspense chillers at which Hitchcock excels, and judging from the unfinished script (Hitchcock is keeping the dramatic end a secret until the actual day of shooting), it should be one of his most pleasantly terrifying. It deals with the cross-country chase of authorities on the heels of a saboteur who wrecks a California airplane factory. Bob Cummings plays the role of Barry Kane, a young airplane worker unfairly suspected of the crime who eventually (we hope) leads the authorities to the headquarters of the gang of saboteurs. Priscilla Lane is Patricia Martin, the girl who first mistrusts Barry, then gains faith in him, and ultimately learns to love him.

From beginning to end, the characters in Saboteur definitely are established as Americans. Hitchcock had a reason for this, disturbing as it is. He felt it was high time we were jolted into the realization that within our own people are men and women who are traitors to their country. Not all the dirty work in war, he preaches through the story, is done by foreign agents.

Casting always is a high point in any Hitchcock picture. He nurses a phobia for presenting new faces, or if new faces are not available, he resorts to switch casting and make-up. Thus Priscilla and Bob were chosen as being typical young Americans in their field of work—Priscilla as a billboard model and Bob as an airplane worker. Clem Bevans, always seen as a comic, became a heavy for Saboteur. Alan Baxter's dark good looks (a la gangster) are masked by a blandly blond make-up, and Norman Lloyd, unknown to the screen, was brought from the New York stage for a pivotal character.

"Let the public see an established hero or heavy in those roles and you've tipped off your whole story," Hitchcock said. "I try to keep 'em guessing by never being sure who is the hero and who is the heel."

The extent to which Hitchcock will go in unorthodox casting was shown by his desperate efforts to get genial Guy Kibbee for the head of the saboteur ring. Kibbee loved the idea, but unfortunately was tied up with other pictures.

Another Hitchcockian quirk is his unfailing courtesy to his actors and crew. It's always "Mr. Bevan," "Miss Lane" or "Mr. So-and-So," never "Clem," "sweetheart" or "you." For one shot he wanted an unexpected change in camera angle. Many a director would have barked curt orders. Hitchcock said quietly, "Mr. Valentine, if it would not inconvenience you, could we move up when the door opens and back as he enters the room?"

Mr. Valentine replied, "Brother, you're a cinch!"

Only God can make a tree but occasionally Hitchcock tries to improve upon the result. A vast stretch of desert as Nature made it, for instance, did not strike him as sufficiently photogenic for one sequence. Without ado, he calmly recreated the entire scene on a Hollywood sound stage, adding such boulders, highway and brush as the exacting eye of the camera demanded. It was on this set the dust storm, carefully prepared by Frank, was staged. Giant fans whipped the air into a gale as tons of finely powdered Fuller's Earth were blown about in a choking, gritty "mess." Hitchcock, cameraman, electricians, carpenters, prop men et al, save two people, wore protective clothing and face masks. The two were Bob and Priscilla. For three straight days they "struggled" through the storm seeking shelter, their eyes burning, throats choking and skins lashed by the wind and dust.

After the first take, Priscilla staggered to a chair for rest. Solicitously, someone suggested she stuff her ears, nose and throat with protective cotton.

"Oh, sure," she wailed. "And I suppose I breathe through my big blue eyes?"

The final take on the third day found them stumbling into a roadside billboard. Through the hellish, swirling fog of dust they read its message: The Perfect Tribute. A Fine Funeral for $45 Complete.

"Sold!" said Bob. "All I have to do is lie down!"

It came from the heart, for Bob took a mighty beating in Saboteur. Not only did he endure the three-day dust storm but in other sequences spent two days in the tank (action called for him to dive from a bridge into a river) and the succeeding three days in scenes showing him wet and shivering.

It was while Bob was floundering around in the tank that Hitchcock delivered the final insult. Someone remonstrated it was a dirty trick to keep Cummings immersed while he, Hitchcock, discussed camera angles.

"It should be done to all actors," Hitchcock said gravely, but with a twinkle in his round blue eyes.

"What? Drown 'em?"

"No. Wash 'em!"

Some day, Bob vows, he'll have revenge.

No detail, it seems, is too trivial to escape Hitchcock's all-seeing eye. A certain scene showed dinner preparations in the home of an aircraft worker. Suddenly the director stopped the set dressing. "Those six pork chops are too anemic," he complained, and asked the prop man if he knew any aircraft factory workers. The prop man proudly answered that one of his buddies used to work for a local factory. "How long ago?" asked Hitchcock. Two years, the man said.

"Ah," said Hitchcock, "but times have changed. Wages have sky-rocketed and the boys are getting in plenty of overtime. So now they're buying better furniture, better clothing—and bigger pork chops. Believe me, I know."

Hitchcock did know. In following an old Hitchcock custom—research into the lives of the living counterparts of his screen characters—he had dined that very week in the homes of three aircraft mechanics! The pork chops were thick. Plenty thick.