Here’s a interesting article I stumbled across in the July 1941 issue of Motion Picture magazine:

IS FONTAINE’S FUTURE IN HITCHCOCK’S HANDS ?

JOAN WAS GETTING NOWHERE FAST TILL HITCHCOCK GAVE HER ROLE OF “REBECCA.” HE MADE HER AN ACE ACTRESS. NO WONDER SHE DOESN’T WORK FOR ANYONE ELSE!

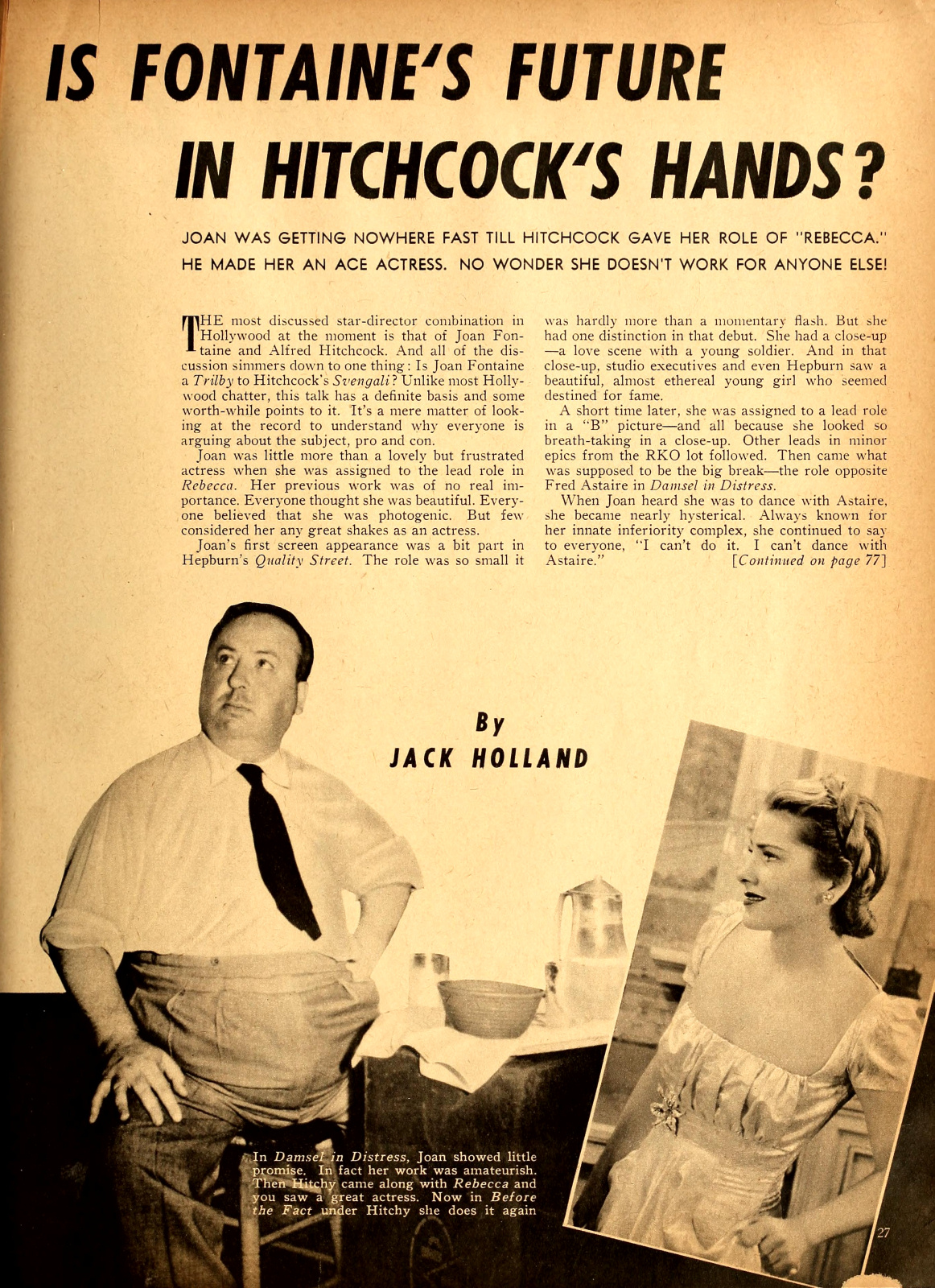

The most discussed star-director combination in Hollywood at the moment is that of Joan Fontaine and Alfred Hitchcock. And all of the discussion simmers down to one thing : Is Joan Fontaine a Trilby to Hitchcock’s Svengali ? Unlike most Hollywood chatter, this talk has a definite basis and some worth-while points to it. It’s a mere matter of looking at the record to understand why everyone is arguing about the subject, pro and con.

Joan was little more than a lovely but frustrated actress when she was assigned to the lead role in Rebecca. Her previous work was of no real importance. Everyone thought she was beautiful. Everyone believed that she was photogenic. But few considered her any great shakes as an actress.

Joan’s first screen appearance was a bit part in Hepburn’s Quality Street. The role was so small it was hardly more than a momentary flash. But she had one distinction in that debut. She had a close-up —a love scene with a young soldier. And in that close-up, studio executives and even Hepburn saw a beautiful, almost ethereal young girl who seemed destined for fame.

A short time later, she was assigned to a lead role in a “B” picture—and all because she looked so breath-taking in a close-up. Other leads in minor epics from the RKO lot followed. Then came what was supposed to be the big break—the role opposite Fred Astaire in Damsel in Distress.

When Joan heard she was to dance with Astaire, she became nearly hysterical. Always known for her innate inferiority complex, she continued to say to everyone, “I can’t do it. I can’t dance with Astaire.”

But she did, and everyone knows the rest of the story. Damsel in Distress was a distressing picture, and the legend of Joan Fontaine as an actress was catalogued as a mistake on the part of Hollywood. It was a long dry spell before Rebecca came along. Joan was more or less forgotten. That was before Alfred Hitchcock took hold of the reins.

When Joan went into Rebecca, she was not only a very nervous and highly emotional young lady, but she was scared stiff. She had never had any confidence in herself. Her ambition had been defeated at every turn. Hollywood had dismissed her with a casual nod. Then, suddenly, to be told that she was to work under one of the finest directors in the business was more than a shock. It was something like a complete emotional upheaval.

The only thing that helped was that she knew Hitchcock personally. She had met him at a Hollywood dinner party among the English colony. She had been intrigued by the man, but she had never so much as thought about starring in one of his pictures. So, instead of being ecstatically thrilled, she became more conscious of herself than ever and even more sensitive.

The story of Joan’s getting the part in Rebecca has probably been told before in many versions, but the real and inside version has not been clearly discussed.

David O. Selznick was giving a dinner party one night for Hitchcock. Joan was invited. She knew that Selznick was trying to find a girl to play the wife in Rebecca, but she didn’t even think that she was a candidate for the part. Since she didn’t have to worry about such an opportunity, she was quite gay and very appealing. During the dinner, Selznick kept eyeing Joan. Then he would look at Hitchcock. The director was also paying marked attention to her. Finally, Selznick whispered to Hitchcock, “She’s the girl.” The reply was, “Definitely.”

The next morning the news came out that Joan Fontaine had been signed for the part. Everyone was stunned. Joan was floored. She was glad, however, that she had known nothing about the decision at the dinner party. If she had, she would probably have been so nervous and so self-conscious that she would have been a dud.

On the first days of Rebecca, Hitchcock knew he had a job to do with Joan. Since he was well aware of her shyness and reserve, he decided that the thing for him to do was to capitalize on that shyness and reserve. If he could keep her conscious of herself, he would get the character out of her.

After the first week of production of Rebecca, Joan was really upset. From the opening gun on, Hitchcock had mercilessly grilled her. He had criticized her work harshly, bluntly. He had pushed her more and more into her shell. Never for a moment did he permit her to let up. Half of the time she was in tears. The other half she was working like a dog to please this man whom she thought she knew. And more and more she became sensitive, frightened, and absolutely devoid of confidence. And more and more she became the real Mrs. Max de Winter.

All of this time, Hitchcock smiled to himself. While he was ripping into her when she did a bad scene, he was becoming even surer that he was getting the results he wanted. He wasn’t anxious to be harsh and domineering, but he had to create a character and he had to keep Joan just as she was. So, without realizing it, he was, in reality, already a Svengali.

The amazing part of this peculiar set-up between star and director was that not once did Joan feel like walking out of the picture. Not even in her most harrowing moments did she think of that. She listened to Hitchcock, let him brow-beat her, and was determined to give him what he wanted. She knew that this was her chance to show everyone that she did have ability, and she knew that she was working with a man who could help her prove herself. Therefore, any suffering was worth it if success were to be the answer.

Of course, it wasn’t easy for Joan. Not only was she continually nervous and high-strung, but she was ill so much of the time. Ever since she was a child, she had been frail and in poor health. Several times she had to be off the picture because of illness. But she stuck it out. She had the courage to refuse defeat. That was no news to Hitchcock. He always knew she could show up the doubting Thomases. And, by gad, sir —he’d make her show them.

When Rebecca was previewed, the press went wildly batty about Joan’s work. She wept with joy. She had proved to everyone now that she was an actress. But in her heart, she knew that she could not have done it without Hitchcock and his stern, unrelenting methods.

Some time passed. Rebecca was still winning praises. So was Joan. But people began to wonder just why she wasn’t doing anything else. Then came the announcement that she was to appear in Back Street. That was great. She was just the type. She would be a sensation as the woman who gave up her life for love. Reporters settled down to get ready to interview Joan on her new picture. Hollywood had already begun to ask: “Can she do it again? Is she a one picture actress?” Some even said hopefully, “Well, at least, she doesn’t have to depend on Hitchcock now.”

Then the bomb exploded. Joan refused to do the picture. Selznick was quite annoyed with her. Universal was more than annoyed. But she held her ground. She would not do the part. Sure, the role was a good one. She would be co-starred with Charles Boyer. She’d have a good director in Robert Stevenson. It was to be an expensive film. But she said, “No !” And gave no reason.

Alfred Hitchcock, however, could guess the reason. Joan, frankly, knew that he knew it. It was just a case that she had attained success because of one director. She was still not sure enough of herself or her ability to take the chance of throwing that success away in one picture. Back Street was to have been her test. If she flopped—it was all over. Therefore, she would wait—for Hitchcock.

Hollywood began to see through the refusal after a while. At first the natives thought it was because she had been so ill for the past months, for everyone knew about the serious operation she had undergone some time back. But illness wasn’t the real reason. So—was she really a Trilby ? This might very well have spelled the end of Joan Fontaine’s career. It had made many producers afraid to take a chance with her.

Undoubtedly, she would have been dismissed again if it hadn’t been for Hitchcock.He had just finished doing a picture at RKO, Mr. and Mrs. Smith. In preparation was a film called Before the Fact, a psychological thriller, the type of thing he does best. Cary Grant was cast for the male lead. But the role of the wife was open. And there was only one person for it as far as he was concerned—Joan Fontaine. When he approached the producer about Joan, a great to-do was raised.

“Fontaine isn’t right for it,” Hitchcock was told. “I’ve sounded out others in the studio, and they all agree with me. No, I don’t think she’ll do.”

Hitchcock was adamant, however. He insisted that Joan be given the part and even went so far as to say that he would not to the film without her. Sure, he knew he was giving himself extra work. He would have to be very careful with Joan this time. He believed in her and saw her in the part.

So Joan was cast in Before the Fact. Some were surprised again but not for long. The talk was open and above-board now. “Oh, well, didn’t I tell you? She can’t do anything without Hitchcock.”

It was a different Joan that began work again, though. She had more poise. She wasn’t entirely too confident of herself, but she didn’t have as many doubts as she had had before. And instinctively, she knew that Hitchcock would bring out the best in her and would complete her character reformation.

As for Hitchcock, he knew he had a definite responsibility. A publicity man at RKO said to me just recently: “All during the production of Before the Fact, Hitchcock felt considerable responsibility for Fontaine. He felt that it was his job to see that she did not fail to repeat her success in Rebecca.”

To see that Joan made another solid hit, Hitchcock adopted some typical technique, typical, at least of him. When he wanted to get her mind off anything that was bothering her and to put her in the proper mood for a scene, he would start to be very blunt with her. He’d usually say, “All right, dopey”—that being his pet name for her—”you can do better than that. What’s holding you back? Come on!” His voice would become more and more intense, he would move closer and closer to her while he was directing her, and she would become so nervous that she would do the scene exactly as he had told her to.

Occasionally, Hitchcock resorted to a subterfuge. He would be rehearsing Joan in a scene. When he felt that she was playing the sequence flawlessly, he would say, “Let’s rehearse it again.” But, instead and without her realizing it, he would wave his hand and the scene would be filmed. Everyone on the set knew that when he carelessly raised his hand it meant a take without the players knowing it. This system worked wonders with Joan in many cases. She would have finished playing the scene for the supposed rehearsal, she’d turn to him and say, “I’ve got it now, can we take it?” And he’d smile and say, “We just did.” Then to the cameraman, “Print that one.”

On another occasion, he wanted Cary Grant to appear extremely tense and angry. He had drilled and drilled them. But the scene wasn’t quite as he wanted it. So he turned to his assistant director and said, “See if you can make these dopes play this thing intelligently.” He walked off the set smiling. In a few moments he returned, and Grant and Joan really did some tall acting to prove to Hitchcock that they could do the scene. He had made them so nervous, that he captured just the right mood.

I was out on the set one day when Joan was supposed to be cutting a hedge with one of those long hedge shears. A shadow crossed in front of her. Supposed to be frightened, she dropped the shears. When they fell, they just missed hitting her foot. Three times the scene was shot, and each time it seemed certain that the shears would injure her. Joan was getting very nervous. Finally, the assistant turned to Hitchcock and said, “Shouldn’t we give her a stand-box to protect her?” (A stand-box is a wooden affair with holes cut in it for the player’s feet. By using this, the sharp instrument would have fallen on wood and not on Joan’s feet.) Hitchcock answered, “No. I want her to be frightened and those shears are helping to create the illusion.” The assistant then said, “But what if they do fall on her feet?” Hitchcock said very definitely, “They won’t. Besides, there’s only going to be one more ‘take.'”

Several times Joan got too much in the mood. She became very confident and over-exuberant. To prevent the scene from tinging on the theatrical, as a result, Hitchcock usually created some off-stage noise. Joan would have to stop then. When he told her to do the scene over again, she would become nervous and bobble a part of it. With surprising nonchalance, he would say to her, “All right, dopey, what’s the matter with you ? You did it once. Now surely you can read the lines again.”

But Hitchcock wasn’t all badgering. Many times he would take her aside and talk to her privately for as long as fifteen and twenty minutes. After such conversations, Joan would return to the set and deliver an astounding performance … He was also considerate when he was directing her in a highly dramatic scene. On a later visit to the studio I found the set closed to everyone, including Hitchcock’s secretary, because Joan was spending the day crying for some sequences. And when Hitchcock closes a set, no one is admitted. He keeps only a skeleton crew and cuts off the view of the set from everyone possible. At one time in a living-room scene, he even closed the drapes so that members of the crew could not see what was going on.

Often Hitchcock becomes so engrossed in directing his players in a tense moment that he is almost sitting on their laps. More than once the cameraman had to tell him that he could be seen in the camera. But this system creates the tension he is after.

Despite the fact that he kept Joan in a tension every single day, he was considerate of her. He realizes she is not very strong, and he gives her every chance possible to rest after a scene. During lunch time, she always goes to her dressing-room to lie down. So it’s easy to see that if Hitchcock were a demon in disguise, he would not stop to consider anything as “insignificant” as his pet star’s health.

During Rebecca, Joan was too nervous to let go of her real sense of humor. But in Before the Fact, she gave Hitchcock back much of the kidding and badgering he gave her. In one scene the telephone was supposed to ring and Joan, eager but yet afraid to answer it, was supposed to wait just a second before she actually got up from the table to go to the phone.

“I want you to wait just a bare second,” Hitchcock told her. “Just the tiniest bit of a second.”

Joan smiled and said, “Do you mean about one-thirty-sixth of a second?”

The mere fact that she could occasionally banter a little herself is conclusive proof that she was becoming more confident.

In spite of this gruelling direction—the type that would send most stars into violent rages—Joan idolizes Hitchcock. Not only has he given her more confidence in herself, but he has made her see what she was without him. Several times recently, she has seen some of her earliest pictures. When she compares them with Rebecca, she needs no more proof. No wonder Hitchcock is, to her, nothing short of a god. No wonder she still feels that her career is safer under his direction. She realizes he has used tricks to get the performances out of her, but she also realizes that without the knowledge of those tricks, she would never be able to be completely confident.

Another thing he has done for her is to teach her to analyze her scenes. During production of Before the Fact, she came to him and asked him about his reaction to a certain sequence. Should the girl do this or should she do that? What does he think about this interpretation? Her role became more than dialogue to her. It became a real person, one to be studied.

As for Hitchcock’s impression of her, he thinks she has great ability. He doesn’t think he has done any more than mould that ability, to teach her how to project it. And he doesn’t hesitate to say that if she weren’t talented, he could have done nothing for her.

So you have the new Joan Fontaine. A girl who is more certain of her success. A girl who knows how to use her gifts. A girl who is losing her inferiority complex gradually. A girl who has been transformed from an inept young beauty to a gifted dramatic actress.

Is Joan Fontaine a Trilby to Hitchcock’s Svengali, then? The question cannot be finally answered until she is seen in a picture directed by someone else. But up to this point, what do you think?