I can’t recall ever seeing this article reproduced before, so I thought I’d share it with you :)

“Movieland’s Spy Master” appeared in the Montana Standard (08/Nov/1942) and looks to have originally been published in Every Week Magazine. The LIFE article it mentions is the well-known “Have You Heard?” photo essay.

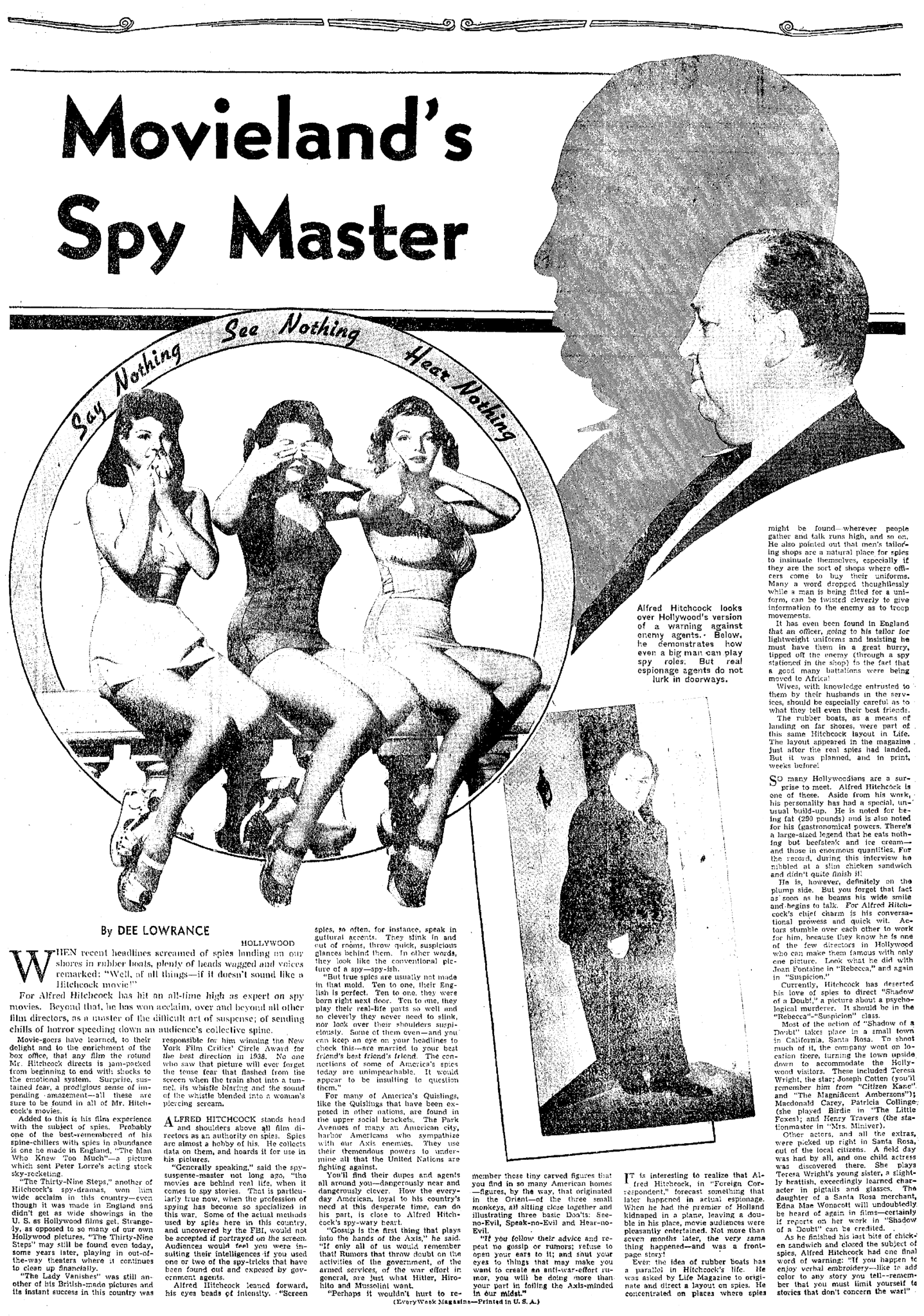

Movieland’s Spy Master

When recent headlines screamed of spies landing on our shores in rubber boats, plenty of heads wagged and voices remarked: “Well, of all things — if it doesn’t sound like a Hitchcock movie!”

For Alfred Hitchcock has hit an all-time high as expert on spy movies. Beyond that, he has won acclaim, over and beyond all other film directors, as a master of the difficult art of suspense; of sending chills of horror speeding down an audience’s collective spine.

Movie-goers have learned, to their delight and to the enrichment of the box office, that any film the rotund Mr. Hitchcock directs is jam-packed from beginning to end with shocks to the emotional system. Surprise, sustained fear, a prodigious sense of impending amazement — all these are sure to he found in all of Mr. Hitchcock’s movies.

Added to this is his film experience with the subject of spies. Probably one of the best-remembered of his spine-chillers with spies in abundance is one he made in England, “The Man Who Knew Too Much” — a picture which sent Peter Lorre’s acting stock sky-rocketing.

“The Thirty-Nine Steps,” another of Hitchcock’s spy-dramas, won him wide acclaim in this country — even though it was made in England and didn’t get as wide showings in the U.S. as Hollywood films get. Strangely, as opposed to so many of our own Hollywood pictures, “The Thirty-Nine Steps” may still he found even today, some years later, playing in out-of-the-way theaters where it continues to clean up financially.

“The Lady Vanishes” was still another of his British-made pictures and its instant success in this country was responsible for him winning the New York Film Critics’ Circle Award for the best direction in 1938. No one who saw that picture will ever forget the tense tear that flashed from the screen when the train shot into a tunnel, its whistle blaring and the sound of the whistle blended into a woman’s piercing scream.

Alfred Hitchcock stands head and shoulders above all film directors as an authority on spies. Spies are almost a hobby of his. He collects data on them, and hoards it tor use in his pictures.

“Generally speaking,” said the spy-suspense-master not long ago, “the movies are behind real life, when it comes to spy stories. That is particularly true now, when the profession of spying has become so specialized in this war. Some of the actual methods used by spies here in this country, and uncovered by the FBI, would not be accepted if portrayed on the screen. Audiences would feel you were insulting their intelligences if you used one or two of the spy-tricks that have been found out and exposed by government agents.

Alfred Hitchcock leaned forward, his eyes beads of intensity. “Screen spies, so often, for instance, speak in guttural accents. They slink in and out of rooms, throw quick, suspicious glances behind them. In other words, they look like the conventional picture of a spy — spy-ish.

“But true spies are usually not made in that mold. Ten to one, their English is perfect. Ten to one, they were born right next door. Ten to one, they play their real-life parts so well and so cleverly they never need to slink, nor look over their shoulders suspiciously. Some of them even — and you can keep an eye on your headlines to check this — are married to your best friend’s best friend’s friend. The connections of some of America’s spies today are unimpeachable. It would appear to be insulting to question them.”

For many of America’s Quislings, like the Quislings that have been exposed in other nations, are found in the upper social brackets, The Park Avenues of many an American city, harbor Americans who sympathize with our Axis enemies. They use their tremendous powers to undermine all that the United Nations are fighting against.

You’ll find their dupes and agents all around you — dangerously near and dangerously clever. How the everyday American, loyal to his country’s need at this desperate time, can do his part, is close to Alfred Hitchcock’s spy-wary heart.

“Gossip is the first thing that plays into the hands of the Axis,” he said. “If only all of us would remember that! Rumors that throw doubt on the activities of the government, of the armed services, of the war effort in general, are just what Hitler, Hirohito and Mussolini want.

“Perhaps it wouldn’t hurt to remember those tiny carved figures that you find in so many American homes — figures, by the way, that originated in the Orient — of the three small monkeys, all sitting close together and illustrating three basic Don’ts: See-no-Evil, Speak-no-Evil and Hear-no-Evil.

“It you fellow their advice and repeat no gossip or rumors; refuse to open your ears to it; and shut your eyes to things that may make you want to create an anti-war-effort rumor, you will he doing more than your part in foiling the Axis-minded in our midst.”

It is interesting to realize that Alfred Hitchcock, in “Foreign Correspondent,” forecast something that later happened in actual espionage. When he had the premier of Holland kidnapped in a plane, leaving a double in his place, movie audiences were pleasantly entertained. Not more than seven months later, the very same thing happened — and was a front page story!

Even the idea of rubber boats has a parallel in Hitchcock’s life. He was asked by Life Magazine to originate and direct a layout on spies. He concentrated on places where spies might be found — wherever people gather and talk runs high, and so on. He also pointed out that men’s tailoring shops are a natural place for spies to insinuate themselves, especially if they are the sort of shops where officers come to buy their uniforms. Many a word dropped thoughtlessly while a man is being fitted for a uniform, can be twisted cleverly to give information to the enemy as to troop movements.

It has even been found in England that an officer, going to his tailor for lightweight uniforms and insisting he must have them in a great hurry, tipped of the enemy (through a spy stationed in the shop) to the fact that a good many battalions were being moved to Africa!

Wives, with knowledge entrusted to them by their husbands in the services, should be especially careful as to what they tell even their best friends.

The rubber boats, as a means of landing on far shores, were part of this same Hitchcock layout in Life. The layout appeared in the magazine just after the real spies had landed. But it was planned, and in print, weeks before!

So many Hollywoodians are a surprise to meet. Alfred Hitchcock is one of these. Aside from his work, his personality has had a special, unusual build-up. He is noted for being fat (230 pounds) and is also noted for his gastronomical powers, There’s a large-sized legend that he eats nothing but beefsteak and ice cream — and those in enormous quantities, for the record, during this interview he nibbled at a slim chicken sandwich and didn’t quite finish it!

He is, however, definitely on the plump side. But you forget that fact as soon as he beams his wide smile and begins to talk. For Alfred Hitchcock’s chief charm is his conversational prowess and quick wit. Actors stumble over each other to work for him, because they know he is one of the few directors in Hollywood who can make them famous with only one picture. Look what he did with Joan Fontaine in “Rebecca,” and again in “Suspicion.”

Currently, Hitchcock has deserted his love of spies to direct “Shadow of a Doubt,” a picture about a psychological murderer. It should be in the “Rebecca”-“Suspicion” class.

Most of the action of “Shadow of a Doubt” takes place in a small town in California, Santa Rosa. To shoot much of it, the company went on location there, turning the town upside down to accommodate the Hollywood visitors. These included Teresa Wright, the star; Joseph Cotten (you’ll remember him from “Citizen Kane”, and “The Magnificent Ambersons”); Macdonald Carey, Patricia Collinge (she played Birdie in “The Little Foxes); and Henry Travers (the station master in “Mrs. Miniver”).

Other actors, and all the extras, were picked up right in Santa Rosa, out of the local citizens. A field day was had by all, and one child actress was discovered there. She plays Teresa Wright’s young sister, a slightly brattish, exceedingly learned character in pigtails and glasses. The daughter of a Santa Rosa merchant, Edna Mae Wonacott will undoubtedly be heard of again in films — certainly if reports on her work in “Shadow of a Doubt” can be credited.

As he finished his last bite of chicken sandwich and closed the subject of spies, Alfred Hitchcock had one final word of warning: “If you happen to enjoy verbal embroidery — like to add color to any story you tell — remember that you must limit yourself to stories that don’t concern the war!”