70 years after his death, Eliot Stannard remains an enigma.

No-one knows how many films he wrote scenarios or screenplays for — the Internet Movie Database currently lists 168 writing credits, other sources state around 80, whilst an advertisement for Filmophone Limited which appeared in The Times on 19 December 1928 stated Eliot had by then “written over 400 scenarios”. Whatever the true figure, he was one of the most prolific British film writers of the silent era.

No-one seems entirely sure what happened to him. We know from his death certificate that he died aged 56 on 21 November 1944 at St. Mary Abbot’s Hospital and that the cause of death was myocardial degeneration and chronic rheumatic myocarditis. However, what was Eliot doing prior to his death? Was he still working as a “film scenario writer” (the occupation given on his death certificate) or, as some claim, did he spend his final years working in an office and inventing a convoluted filing system which only he understood?

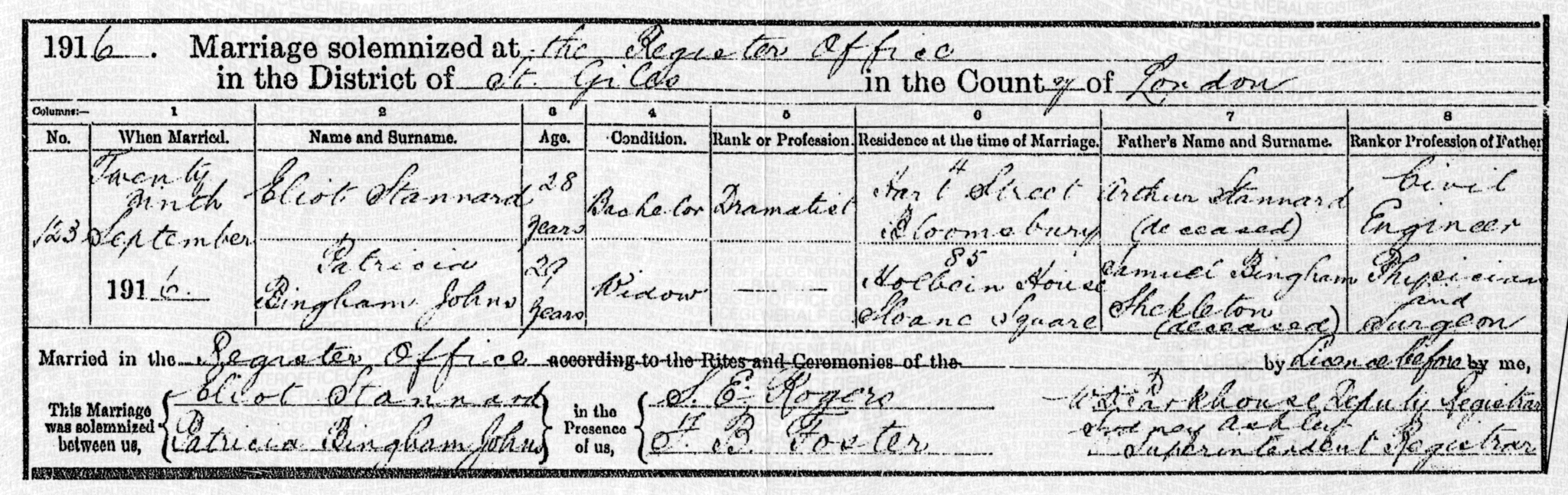

Even the few facts we do know of his life become tales of intrigue if we examine them too closely. The Internet Movie Database claims without ambiguity that he married Patricia Bingham-Johns, yet you will struggle to find that person in the official historical records. Seemingly Patricia was never born and she never died – she existed only for the 15 years that Eliot lived with her as her husband, and then she vanished from the face of the earth. When we dig even deeper, we tumble into a rabbit hole as we discover that Eliot was probably never actually married (at least not in the legal sense). And yet, as clear as day, here is his marriage certificate to the woman who never existed…

Eliot Cardella Stannard was born on 1 March 1888 in Wansworth, London, along with a twin sister, Violet Mignon Stannard. As well as his twin, there was an older sister, Audrey Noel Palmer Stannard (1884-1912), a sister who died before his birth, Dorothy Katharine Palmer Stannard (1885-1886), and a younger sister, Olive Nancy Stannard (1895-1975).

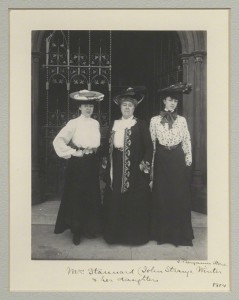

His father, Arthur Stannard (c1854-1912), was a civil engineer and company director. His mother, Henrietta Eliza Vaughan Stannard (1856-1911) née Palmer, was a popular Yorkshire-born novelist who published under the unusual pseudonym John Strange Winter. Henrietta was the first president of the Writers’ Club (1892) and was the president of the Society of Women Journalists from 1901 to 1903.

Despite Henrietta’s success as a writer, her husband (who also seems to have acted as her agent) declared bankruptcy in 1908. Digging around in the records, it seems he transferred the deeds of the family home to one of his daughters prior to bankruptcy, presumably so that the house wouldn’t be seized as an asset.

At the time of 1911 Census, we find 57-year-old Arthur working as the “Managing Director of Toilet Preparation Company”, which presumably was a company manufacturing bathroom fixtures. 23-year-old Eliot is listed as the Assistant Manager.

Henrietta, who had been ill for some time, passed away in December 1911. Arthur died the following year in October 1912.

Following his father’s death, Eliot appears to have taken over the management of the company but it didn’t last long – he declared bankruptcy in November 1913. Within a year, Eliot was channelling the skills of his mother and had begun writing.

On 29 September 1916, Eliot Stannard stood in the Registry Office of St. Giles, London, and married 29-year-old widow, Patricia Bingham Johns, resident of 85 Holbein House, Sloane Square, London. The couple appear to have lived together at Holbein House until around 1930 and then they seemingly separated but didn’t divorce.

However, as previously noted, Patricia Bingham Johns never existed. You won’t find details of her previous marriage, presumably to a Mr. Johns, no matter how hard you look. You won’t find details of her birth or her death. Nor will you find any definite record of her prior to her marriage to Eliot nor after they separated – there are “Patricia Stannard”s listed in the Electoral Registers, but none appear to the person who lived with Eliot.

So, who was this mysterious woman who stood next to Eliot in the Registry Office in September 1916?

The only clue to her real identity is on the marriage certificate – she gives her father’s name and occupation as “Samuel Bingham Shekleton (deceased)” and “Physician and Surgeon”.

Samuel Bingham Shekleton was born around 1849, trained to become a doctor, and married Mary Ann Louisa Smith in February 1881. They had several children, but none of them were named Patricia, nor were any of them born in 1887, the year indicated on Eliot’s marriage certificate.

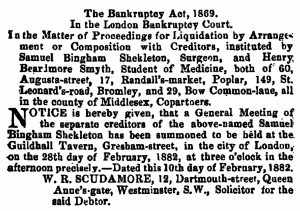

A year after their marriage, the London Gazette reported that surgeon Samuel Bingham Shekleton and medical student Henry Beardmore Smyth had jointly declared themselves bankrupt. Quite how a surgeon had managed to run up such debts is uncertain, but we’ll soon see that Samuel’s ethical behaviour left a little to be desired!

Over the next few years, Samuel appears to have practised at a variety of addresses in the London area and, by the late 1880s, the family was living in Stratford, where of course Alfred Hitchcock’s parents and uncles were busy running a number of greengroceries and fishmongeries. It was here that, seemingly without warning, Samuel Bingham Johns vanished off the face of the earth.

With no money to support her children, Mary Shekleton was soon in difficulty and they were admitted to West Ham Union Workhouse. When the officials at the workhouse were told that Samuel had abandoned his family, they reported the matter to the police and a warrant was issued for Samuel’s arrest.

We next pick up the tale in December 1891 when newspapers in Bristol and Bath reported on the court case of surgeon Samuel Bingham Shekleton, resident at 1 Carlton Place, Bristol. Charged with neglecting his wife and children, the judge adjourned and told Samuel that if he cleared the outstanding debts of £5 13s 9d with the West Ham Union Workhouse, the case against him would be dropped. As there are no further newspaper reports on the matter, we must assume Samuel did just that.

With hindsight, it’s difficult to take Samuel’s claims in court that his wife had a string of young lovers and that he had pleaded on his bended knee for her to stay faithful to him. Mary wasn’t in court and the letter which Samuel produced from her (which astonishingly arrived through his letterbox that very morning!) in which she admitted her infidelity was perhaps a clumsy forgery. However, the judge seems to have believed it.

Samuel continued to live apart from his wife and the next time he surfaces is in June 1899 when the General Medical Council struck him off the Medical Register after he was found “guilty of infamous conduct in a professional respect”. The circumstances were convoluted, but essentially in 1895 he had aided an unqualified person named Julian Averfield Rowland to become a registered doctor under the false name of Edward Joseph Nugent. Rowland had then apparently gone to Australia and worked as a doctor before being exposed as a fraudster.

Presumably Samuel fought against the decision and a June 1905 issue of the British Medical Journal briefly noted that he had been restored to the Medical Register. Two years later, the name of Samuel Bingham Shekleton would become known throughout the entire country.

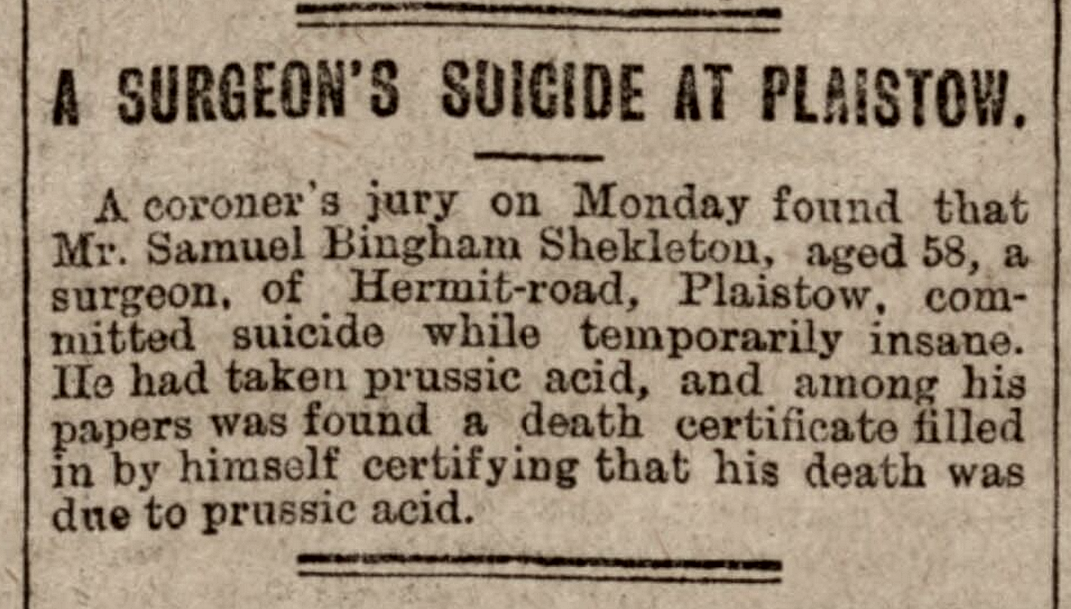

On 7 May 1907, Samuel sat down in his house at 124 Hermit Road, Plaistow, and calmly wrote out a death certificate. He noted that the cause of death was due to “prussic acid poisoning” and then he signed the certificate. Perhaps it was at this point that he double-checked that the small glass bottle of prussic acid, which he habitually carried around with him, was securely hidden in his waistcoat pocket and then he chuckled to himself.

Just under two weeks later, the body of Samuel Bingham Shekleton was discovered in his house. On the floor beside him was the now empty bottle. As the police searched the room, they discovered the death certificate which Samuel had signed on 7 May – the name of the deceased on the certificate was “Samuel Bingham Shekleton”.

The inquest held on Monday 27 May 1907 recorded a verdict of “Suicide Whilst Insane” and noted that the cause of death was “prussic acid poisoning”. Virtually every newspaper in the country printed the incredible story of the mad surgeon who signed his own death certificate.

However, this doesn’t bring us any closer to naming the person who Eliot Stannard married. As Eliot stood in the Registry Office on that day in 1916 and the words “you may now kiss the bride” were uttered, he was almost certainly kissing Samuel and Mary’s first child – Lilian Mary Bingham Shekleton.

Lilian was born around 1882 in Romford, Essex. After her father abandoned the family a few years later, her mother moved to Cardiff and Lilian likely grew up in Wales. It’s difficult to say what kind of person Lilian was, but the historical records reveal a portrait of someone who seemingly had no hesitation in giving false information to the authorities.

In August 1905, a boy named Jack Bingham was born in Carmarthen, Wales. The birth certificate was filled out by the mother who recorded her name as “Lilian Bingham Johns formerly Bingham” – this is almost certainly Lilian Mary Bingham Shekleton. The father is recorded as commercial traveller “Tom Bingham Johns”. However, there is no record that Lilian had married prior to 1905, nor any trace of a “Tom Johns” who might be the father. Unless records are located, we are left with the distinct probability that Jack was an illegitimate child and Lilian invented a fictitious father and marriage to cover that fact from the authorities.

In July 1910, spinster Lilian Mary Bingham Shekleton married Edgar Cecil Cupper in Chelsea, London. If Lilian really had married a “Tom Johns”, she couldn’t declare herself a spinster nor could she enter into a bigamous marriage with Edgar.

The following year, the 1911 Census has Edgar and Lilian living at 116 Keppel Street, Chelsea. Lilian falsely gives her birthplace as “Limerick, Ireland”, perhaps as a reference to her father’s Irish roots. Quite why she felt the need to lie to her husband about her place of birth is uncertain.

At this point you may be asking “how can you be sure Lilian is really the mother of Jack Bingham”? Well, 5-year-old Jack Bingham Johns is to be found living with Edgar’s widowed mother, Eliza, at the time of the 1911 Census. Eliza kept a boarding house and little Jack is listed as a boarder.

Exactly what happened to the marriage is uncertain but Edgar Cecil Cupper left to fight on the battlefields of Europe duing the First World War, serving in the Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment. Upon his return to England, he appears to have moved north to Yorkshire and was married in 1917 to Violet H. Morton. If this is the case, there is no evidence that he had divorced Lilian, so the marriage was bigamous and unlawful. Perhaps, in his absence, Lilian met Eliot Stannard and, when Edgar returned from fighting, his wife had vanished and was now Mrs. Eliot Stannard?

Of Lilian, the next obvious records are those of her death in 1948, when Lilian Mary Shekleton – or “Lilian Mary Shekleton Bingham”, the probate records are unclear as to what her actual name was – passed away in Dorset.

So, we have seen that Lilian called herself “Lilian Bingham Johns” in 1905 and it would seem after her brief marriage to Edgar she decided to call herself “Patricia Bingham Johns”. Quite how she met Eliot Stannard and whether or not he knew the truth of her past we cannot say, but they married in September 1916 and “Patricia” declared herself to be a widow on the marriage certificate.

The couple lived together at Holbein House, Sloan Square, for the next 14 years. Did Eliot ever suspect his wife wasn’t really named “Patricia”? Did he know that their marriage was unlawful due to her bigamy, as she was likely still married to Edgar? Was she still claiming to have been in Limerick, Ireland? We can only speculate for now. What we do know is that the prodigal son returned to the roost in 1930.

Lilian’s son, Jack Vincent Johns, appears to have left home as a lad and went to sea, changing his name to Jack Vincent Bingham. Two of his uncles were also seamen, so perhaps they encouraged him. Jack’s mercantile record notes that he was discharged at the end of June 1929. With nowhere to go, it seems he tracked down his mother.

After several years of appearing alongside Eliot on the Electoral Register as “Patricia Stannard”, the name is amended to “Lilian Patricia Stannard” on the 1930 entry. Also now resident at the same address is Jack Vincent Bingham. This is the last record which places Eliot together at the same address as “Patricia” and we must assume the couple separated at this point. Perhaps the arrival of Jack revealed the truth about Lilian?

Eliot Stannard spent the remainder of his life living in a series of rented rooms, although seemingly not always alone. In 1933, Eliot is living with one “Dorothy Stannard”. Eliot had not married and Dorothy is not a relative. Living in a rented room, Eliot would likely have had to have pretended he was married to Dorothy in order for them to live together.

The 1935 Electoral Register entry supplies a small clue as to who Dorothy might have been, as her name is given as “Dorothy Weychan Stannard”. She was likely Dorothy Agnes Weychan, who was born in 1903 and eventually married a few years after Eliot’s death. She passed away in 1987 aged 84.

Of Eliot’s siblings, his twin sister Violet became one of the first policewomen, joining the London Metropolitan Police in August 1920. According to researcher Helen Barnard, Violet’s job application read “I can not afford to remain without work”. His oldest sister, Audrey Noel Palmer Stannard, had died in 1912. As none of his sisters married and Eliot had no children of his own, Olive Nancy Stannard was the last of the Stannard line — she died on 9 October 1975, aged 80.

If Eliot Cardella Stannard wrote any memoirs, they remain unpublished and there whereabouts unknown. Olive Nancy’s last will & testament makes no reference to any family papers, although tantalisingly there are rumours Olive and Violet did begin writing the memoirs of the Stannard family.

As we’ve already noted, Lilian Mary Bingham Shekleton died in 1948. The woman who seemingly falsified so many official records had the last laugh – despite seemingly being married three times (to the likely fictitious Tom Johns, then Edward Cupper and Eliot Stannard), she is listed as a spinster. Her last will & testament includes items as diverse as a Walter Sickert drawing from 1899 and a .410 gauge shotgun, but not a single mention is made of her only son, Jack.

Notes:

- There is still much that remains uncertain about Eliot’s marriage and the life of Lilian Mary Bingham Shekleton, and the above blog post is partly speculation based on the known facts.

- I’m extremely grateful to Clare, a distant relative of Eliot, for her help in unravelling and interpreting the historical records.

very interested in your posting re Eliot. He may have had a drink problem in hiis later years – have copies of letters about him from a lady describing herself as a concerned friend of his to a distant cousin of mine who was researching Henrietta E V P’s life.

Eliot was my paternal grandfather’s second cousin – they both descended from William Vaughan Palmer, grandson of the actress Hannah Pritchard, (for a long time one of only two women with a memorial in Poet’s Corner.) I hadn’t realised that a mystery hung over Eliot’s marriage though I knew of course – from London telephone directory for instance, that they separated.

Hope you will forgive this intrusion but I appreciated your information as I am compiling an album of family genealogy and related “stories” for younger generations – and the Henrietta Stannard “life” is unusual and a matter of pride ( for me anyway ! ). The toiletrie business by the way was more to do with perfumes etc than bathrooms,- and was set up I think in Dieppe.

Regards, John Davies

Permalink