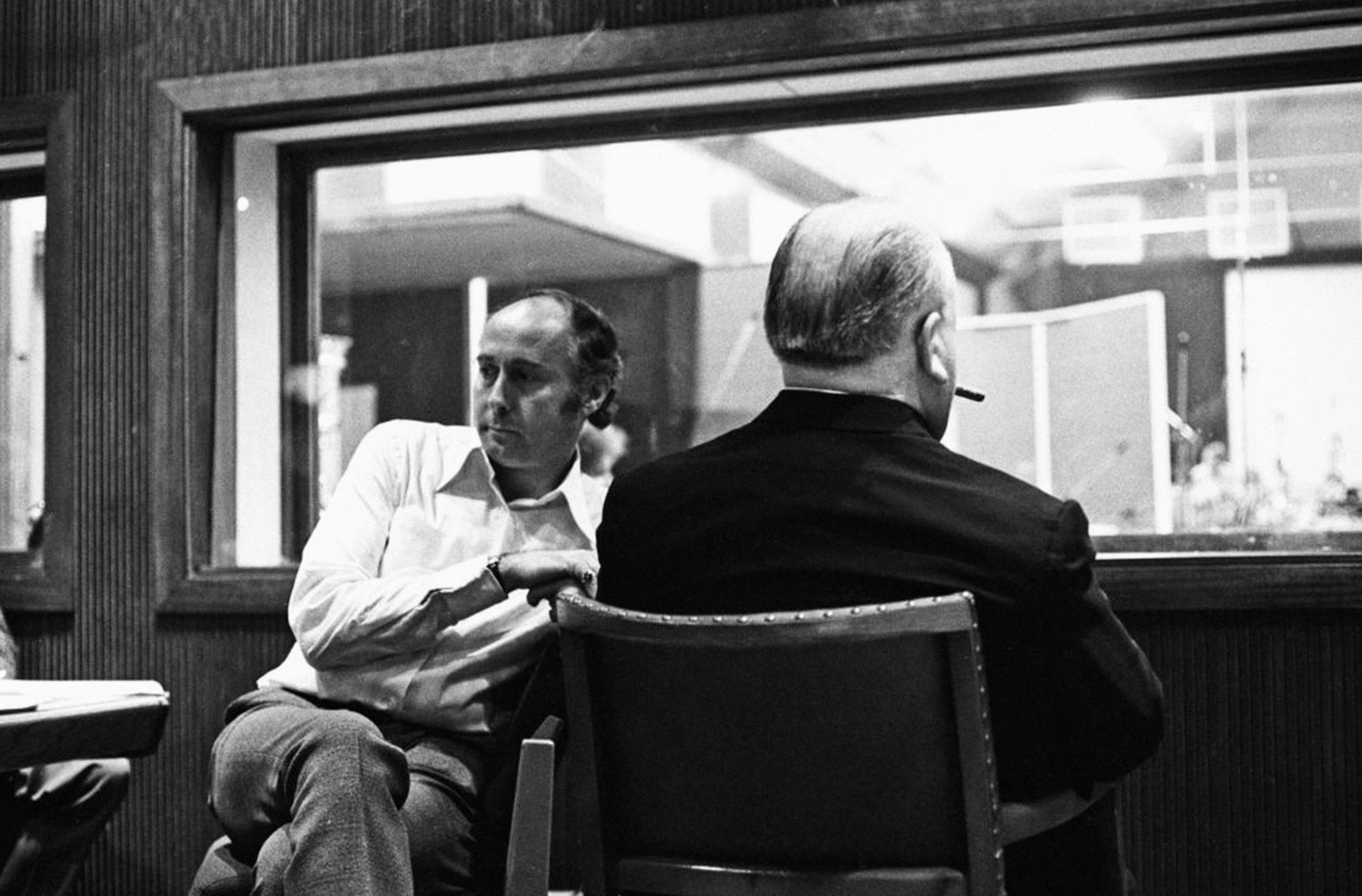

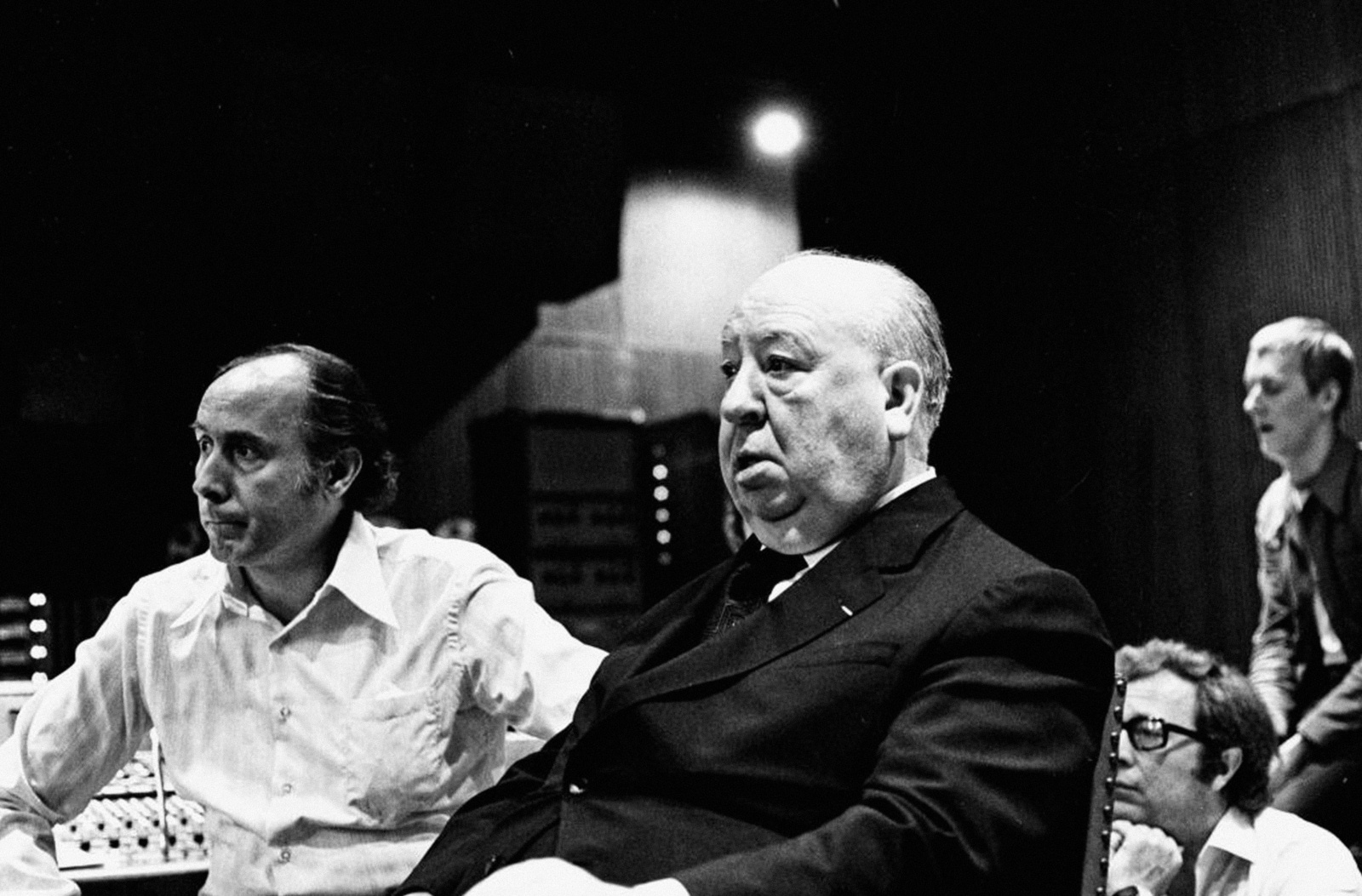

A big “thank you” to film historian Morris Bright (author of Pinewood Studios, 70 Years of Fabulous Filmmaking) for sharing these extremely rare photographs of Hitchcock and composer Henry Mancini, taken in December 1971, which were found hidden away in the Pinewood Studios archives.

Following the breakup of the Hitchcock/Herrmann partnership over the score of Torn Curtain (1966), Hitchcock never again worked with a composer on more than one film.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece, scholar Raymond Foery documents the hectic pace of pre-production for Frenzy (1972). With filming wrapped in London and Pinewood Studios, Hitchcock boarded TWA Flight #761 to Los Angeles at 1pm on Tuesday 26th October, 1971. Alma, who had suffered a serious stroke in London just prior to production starting, had recovered enough to fly back to their Bel Air home earlier in the month, accompanied by her husband’s secretary Sue Gauthier.

Hitch’s trusted assistant, Peggy Robertson, remained in London until the Technicolor labs had finished processing the raw footage. With the film canisters safely stowed, she flew back to America on 10th November. The following day, Hitchcock and editor John Jympson began assembling the initial edit of the film. The process of screenings and further editing continued until 26th November, when Hitchcock dictated a detailed set of final dubbing notes for Jympson. Whilst this process was going on, Hitchcock had to make himself available for a series of press interviews as well as overseeing the work of the translators who were preparing the foreign-language versions of the film.

Meanwhile, Hitchcock had met briefly with composer Henry Mancini and the composer had been sent the final shooting script at the start of November, which would include approximate timings for scenes. In his article about the score, Gergely Hubai notes that it remains uncertain how much guidance the director gave to Mancini, but subsequent events imply that Hitchcock likely gave Mancini free-rein, perhaps in the expectation that he would compose a light pop score to juxtapose the dark undertones of the film. For his work, Mancini was paid a flat fee of $25,000.

With Hitchcock’s final dubbing notes and the reels of film, Jympson flew back to London on 29th November. Prior to the recording of the score, the editor made a series of final adjustments based on the dubbing notes.

Mancini flew into London in time for the recording of the score, which took place over four days in mid_December. Although Mancini later recalled that Hitchcock attending the entire recording, Foery notes that the director and his wife spent only three days in London before departing for France and then a winter break in Marrakech, so it’s likely Hitchcock attended only part of the recordings. However, what he heard was enough to convince him that Mancini’s score was unsuitable.

The composer later stated that he had been surprised by Hitchcock’s manner at the sessions:

It was not so much a matter of his being there as that [Hitchcock] didn’t say much when we were doing [the recordings]. He sat through every piece and nodded approval, and finally, when he was alone in the dubbing room, he decided that it didn’t work. His reason for thinking so, I was told, was that the score was macabre, which puzzled me because it was a film with many macabre things it in. It wasn’t an easy decision to accept, and it was crushing when it happened…

Instead of a light contrapuntal score, what Mancini delivered was dark and brooding, and occasionally reminiscent of Bernard Herrmann. In an interview published in The Guardian, Mancini said:

You want to know how I go about scaring people? Really it is a matter of colours. Of using the orchestra in various combinations to create tension. “Frenzy” is very low-key picture about a neck-tie murderer, and what I have done is to just cut off the orchestra round middle C. There is no high — there are no violins nor high flutes — it is all from there down with ten cellos, ten violas, basses, horns, bassoon, and bass flutes … none of the screeching, high, intense sounds that would be though a little melodramatic today. It is very sparse… there’s not a lot going on, but what there is will, I trust, sound pretty spooky.

With Mancini’s score abandoned, Hitchcock hurriedly hired British composer Ron Goodwin, who was best-known for his scores for 633 Squadron (1964), Where Eagles Dare (1968) and Battle of Britain. Unlike Mancini, Goodwin was provided with detailed notes about which scenes to score and the mood Hitchcock wanted to achieve. Foery notes that “Goodwin later recalled that Hitchcock wanted the music to in no way convey any hint of the horror that was to come”.

Goodwin recorded his score over three sessions at the end of January and beginning of February 1972. The next two weeks were spent overlaying the score and completing the final composite print. By mid-February, Hitchcock had approved the score without requiring any changes and a delighted Goodwin wrote, “I really do appreciate your thoughtfulness and I am most happy to have won your approval.”

A final round of tightening the edit and adjusting the sound mix was completed in time for a studio screening at the end of February. Among those present was Norman Lloyd who famously congratulated Hitchcock, telling him, “It’s the picture of a young man!”

As for Mancini, he somewhat ruefully noted that he had “joined a very exclusive club — the composers-with-scores-dumped club” but fondly recalled in his autobiography how Hitchcock had sent him a case of Château Haut-Brion magnums.

As a footnote, it is sometimes claimed that Hitchcock scolded Mancini by saying, “Look, if I want Herrmann, I’d ask for Herrmann!” However, this is apocryphal and was first stated not by Mancini but by Bernard Herrmann during an interview in the mid-1970s.

Fantastic stuff!!!

Permalink