Without a shadow of a doubt, Hitchcock is one of the most studied and written about directors of all time.

At the time of writing, the Wiki lists 2,372 academic journal articles and over 200 books. From pop-up books through to an entire book about just one short film scene, and from London filming locations through to studies of architecture and set design in his films, it seems as though every aspect of Hitchcock’s life and work has been thoroughly studied, analysed and reanalysed.

For anyone wishing to write about Hitchcock, surely there can be no stone that remains unturned?

Whilst you might think so, I’d like to take the opportunity to highlight four recent books which manage to bring something new to the study of Alfred Hitchcock.

Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films

by Alain Kerzoncuf & Charles Barr, published by the University Press of Kentucky (March 2015)

Charles Barr’s English Hitchcock (2000) remains a key title for anyone interested in Hitchcock’s early career and the book helped to redress the balance which, up until that point, had been firmly in favour of Hitchcock’s American films. Alain Kerzoncuf has long been a friend of the Hitchcock Wiki and, together with Nándor Bokor, contributed a photo essay of filming locations for To Catch a Thief (1955) which has been viewed nearly 12,000 times.

As the title suggests, Hitchcock Lost and Found delves into works that have long remained at the margins of Hitchcock studies and that have received scant attention by other writers. Works such as An Elastic Affair (1930) might appear in the “Hitchcock Filmography” section of a book, but rarely does an author expend more than a sentence on the short film. McGilligan simply notes that it “showcased two young aspirants who had just won acting scholarships and a tryout with the studio”. As a lover of all things trivial, I want to know who these “young aspirants” were and how Hitchcock ended up being involved with such a seemingly minor project. However, McGilligan can hardly be blamed — to date, I’ve yet to find a single reference to An Elastic Affair in any newspaper archive.

Other works have long hovered on the fringes — was Hitchcock really involved with Harmony Heaven and what exactly was his role in Elstree Calling? At best, previously published works have offered mostly speculation. The problem, of course, is that Hitchcock himself rarely talked about these films and, when he did, often dismissed them with remarks such as, “it was a very bad movie”.

As Kerzoncuf and Barr note in the introduction to Hitchcock Lost and Found, they have been careful not to simply repeat details which have already been published and so you will find little information, if any, about Hitchcock’s most well-known films. Therefore, much of information in the book is new and will prove of great interest to Hitchcock scholars.

The book deals chronologically with four periods:

- Hitchcock’s early career from 1920-25, prior to directing The Pleasure Garden.

- Less well-known works from the 1930s, such as Elstree Calling, Mary (the German language version of Murder!) and Lord Camber’s Ladies.

- Hitchcock’s work during the Second World War, including his uncredited work on re-editing British propaganda films for the American market.

- Obscure post-war work, such as the television programmes Tactic, made for the American Cancer Society in 1959, and Hitchcock on Grierson (1969).

In my opinion, this is an essential book for any serious Hitchcock fan and both authors are to be thoroughly congratulated for unearthing so much new content from the archives.

You can find a Google Books preview of Hitchcock Lost and Found at the bottom of this page.

The book has also been reviewed by Devon Powell on his hitchcockmaster blog.

Hitchcock in Context

by Stephane Duckett, published by Moreton Street Books (March 2014)

Who was Alfred Hitchcock?

What sounds like a perfectly straightforward question is a veritable minefield, partly due to the fact that he took great lengths to protect his privacy and rarely let his guard down in interviews. If pressed, Hitchcock would simply trot out one of the many familiar anecdotes, all of which seem to offer some pithy psychological insight…

- His first infant memory was of his mother shouting “BOO!” at him.

- As a child, his father sent him to the local police station with a note. The policeman read the note and took the young boy to a cell and locked him up. A short while later, he was released and the policeman said, “This is what we do to naughty little boys”.

- From then on, he was deathly afraid of the police and refused to learn to drive for fear of being stopped by the police.

- He detested eggs and found them vile.

According to Hitchcock’s biographer, John Russell Taylor, the police station story is “so convenient, accounting as it does for Hitchcock’s renowned fear of the police, the angst connected with arrest and confinement in his films, that one might suspect it of being in the ben trovato [meaning “if it is not true, it is very well invented”] category. And probably Hitchcock has told the story so often he is not sure himself any more if it is true.” In recounting the story, Hitchcock’s age varied widely as did the length of time he was left languishing in the cell.

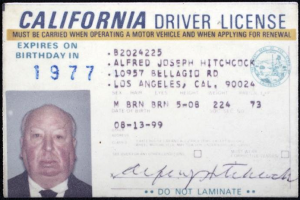

As for his claim that he never drove, this was simply untrue. Hitchcock appears to have held a valid driver’s licence throughout his life, even into his 70s when surely his crippling arthritis would have made driving difficult if not impossible. Having said that, he apparently much preferred to be driven and usually let his wife Alma take the wheel.

The anecdote about eggs was only partially true — what Hitchcock despised was how the raw egg yolk oozed, like blood from a wound (despite scenes like Gromek’s death in Torn Curtain, the director strongly detested violence). When it came to food, he thought nothing of eating poached eggs on toast, a rich soufflé or even a Quiche Lorraine…

In recent years, the belief that Hitchcock was some kind of sadistic misogynistic sexual predator (or, if you’d prefer, “a dirty old man”) had gained in popularity. Much of this stems from the imagination of celebrity biographer Donald Spoto, author of The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (1983) and script consultant for the overly dramatic docudrama “The Girl” (2012), which painted Hitchcock as a stock pantomime villain. Thankfully, the Save Hitchcock blog has done sterling work in busting the myths created by Spoto and “The Girl”.

In the three decades since the release of The Dark Side of Genius, much has been done to critique Spoto’s excesses, including the publication of Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light by Patrick McGilligan. Although not without the occasional error, McGilligan’s biography is more authoritative than Spoto’s (which contains many errors) and he avoids the baseless speculation which blights so much of The Dark Side of Genius.

All of this brings me on to Dr. Stephane Duckett’s Hitchcock in Context, which seemingly appeared out of the blue last year. Duckett, who was born in France but raised in England, is a clinical psychologist based in London and his “fascination with Hitchcock came out of a four-year study on how intensely creative people adapt to ageing”. Whilst he was (to me, at least!) a new name in the field of Hitchcock studies, Duckett is widely published in health sciences and I look forward to future Hitchcock articles by him with great anticipation.

Duckett begins his book by recounting the execution of Edith Thompson. The trial was a cause célèbre in the early 1920s (see the Wikipedia article for further details) and a petition for clemency was signed by nearly a million people — it wouldn’t be unreasonable to speculate that one of the signatures on the petition read “Alfred J. Hitchcock”. However, the petition fell on deaf ears and Thompson went to the gallows on 9 January 1923, despite the fact there was no real evidence that she was complicit in the murder of her husband.

As Duckett notes, Hitchcock knew Thompson and her family, and the repercussions of the case echo down through the director’s work:

[…] a number of Hitchcock’s films feature innocent, or more importantly partly innocent women who nevertheless face the full penalty of the law where public opinion in the form of a disapproval of their lifestyle — particularly sexual — plays a significant part in the determination of their culpability.

There is much I could highlight about the book, but I’ll draw particular attention to Duckett’s important work in detailing the influences of music halls and early serial films on the young Hitchcock — something that I’ve rarely seen mentioned before. Key components of the early serial films were the chase and the cliffhanger, and examples of both appear in many of Hitchcock’s films. Indeed, Hitchcock occasionally likened himself to a switchback railway operator (an early version of the modern rollercoaster) in interviews:

Well, possibly I [am switchback railway operator], in some respects, the man who says, in constructing it, “How steep can we make the first dip?” and “This will make them scream!” If you make the dip too deep, the screams will continue as the whole car goes over the edge and destroys everyone. Therefore, you mustn’t go too far, because you do want them to get off the switchback railway giggling with pleasure, like the woman who comes out of the movie — a very sentimental movie — and says, “Oh, I had a good cry.”

— Alfred Hitchcock (1964)

That Hitchcock held music halls in great affection is perhaps best exampled by the fact he selected two songs from music hall and theatre revues for his 1959 appearance on the BBC radio series Desert Island Discs. Hitchcock likely saw both shows performed when he was a teenager and I strongly doubt either song has ever been picked by another castaway.

When I eventually finished reading Hitchcock in Context, I felt as though I was seeing Hitchcock through fresh eyes and I suspect Duckett has gotten closer to revealing the real Hitchcock than any other author I’ve read before.

As with Hitchcock Lost and Found, this is an essential purchase for anyone interested in learning something new about Hitchcock. In the 12 months that I’ve owned a copy, I’ve already re-read it more times than I’ve ever the copy of Spoto’s The Dark Side of Genius which I’ve owned since the 1980s!

London’s Hollywood: The Gainsborough Studio in the Silent Years

by Gary Chapman, published by Edditt Publishing (July 2014)

As highlighted in Hitchcock Lost and Found, there is much still to explore regarding Hitchcock’s formative years in the film industry and Chapman’s London’s Hollywood helps fill that particular gap.

The book mostly (but not exclusively) details the early history of the Islington Studios, which were opened by Famous Players-Lasky in May 1920 and then taken over a few years later by Michael Balcon’s Gainsborough company.

Whilst not a book specifically about Hitchcock, Chapman weaves the director’s early career into the story of the studio, alongside with the much-maligned director Graham Cutts. As the author notes, Cutts was still being hailed as “England’s greatest director” even as Hitchcock’s early films were being screened and Chapman does much to redress the portrayal of Cutts as an embittered hack, jealous of the young Hitchcock’s talents. In fact, many of the names associated with Hitchcock’s early films — including Ivor Novello, Anny Ondra and Lilian Hall-Davis, to name but a few — established themselves with British film audiences in a Cutt’s film.

Chapman brings together a large amount of primary source material to document the films made at Islington, beginning with The Great Day (given a trade show in 1920) through to the installation of sound recording equipment and the fire which ravaged the building on 18 January 1930, killing employee William Shand.

After completing the book, I must admit I was left wishing Chapman had carried on the history of the studio through the sound era, but perhaps he is planning a second volume!

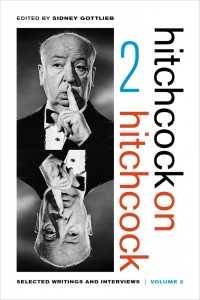

Hitchcock on Hitchcock: Volume 2

edited by Sidney Gottlieb, published by University of California Press (December 2014)

Gottlieb’s collections of Hitchcock’s articles and interviews are essential items for every Hitchcock library and volume 2 of Hitchcock on Hitchcock repeats the format of the first volume, which was published back in 1995.

As is to be expected, this second volume brings together more obscure articles than the first volume and even includes “A New “Chair” Which a Woman Might Fill” — I stumbled across a brief mention of this 1929 journal article in a single local newspaper and eventually managed to locate a copy last summer, assuming it would be a long-lost article, but no, Gottlieb had gotten there first!

With the publication of volume 2, it appears the first volume has undergone a reprint, and I would encourage Hitchcock fans to purchase both for their library.

In reference to Hitchcock being ‘a dirty old man’ and the writing of Donald Spoto, I attended the showing of The Girl and the talk/discussion between Tippi Hedren and Spoto with a live audience at the BFI (2012?). I have always admired Hedren’s acting in both of the Hitchcock films and know a great deal of the history surrounding her relationship with Hitchcock. However, on that particular night I was saddened to see the glamorous Hedren, who was an Octogenarian and yet looking every bit the Hollywood star from a bygone age, choose to be so specific and personal about the details of her relationship with Hitchcock; it felt as if the large room had been greatly diminished to a psychiatrist couch and chair and that ‘we’ the audience was listening to a very private confessional. It just didn’t seem appropriate even though the film would reveal a side to Hitchcock not screened before. I listened uncomfortably to Hedren’s attack, yes attack, on the reputation and character of Hitchcock and felt saddened and slightly uncomfortable, after all this was an actress whose entire career and fame rested on Hitchcock’s discovery of her as a model. I am not saying that what Hedren said was not true, I am sure what happened between her and Hitchcock was in many ways devastating to her and her career, but sometimes their is more than one side to every story and Hitchcock could not speak from the grave. He had no defense and I felt her tone was in some ways malicious. Thankfully, after Hedren relentlessly continued in this vein an American woman in the audience piped up and said ‘o come on give us a break’ and questioned Hendren’s motives. It was fantastic, I felt relieved at last that Spoto’s fawning interview and Hedren’s take on the past had been halted and questioned and that Hitchcock’s character was defended at least to some degree. My feelings about Tippi, however much she had been damaged by what occurred in the early to mid sixties during the filming of The Birds and Marnie (still one of my favourite Hitchcock films) have never been quite the same since.

Permalink