Frenzy (1972)

| From the Master of Shock... A Shocking Masterpiece! | |

/0003.jpg) | |

| Alfred Hitchcock | |

| Alfred Hitchcock | |

| Anthony Shaffer | |

| Arthur La Bern (original novel) | |

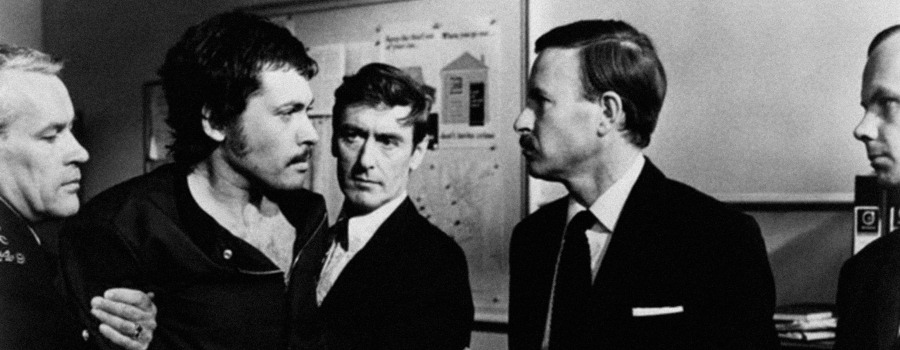

| Jon Finch Alec McCowen Barry Foster Anna Massey Barbara Leigh-Hunt | |

| Ron Goodwin | |

| Gilbert Taylor Leonard J. South | |

| John Jympson | |

| 116 minutes | |

| colour (Technicolor) | |

| mono (Westrex Recording System) | |

| 1.85:1 | |

| Universal Pictures | |

| Universal Pictures | |

| DVD & Blu-ray | |

Synopsis

After the brutal murder of his ex-wife, down-on-his luck former RAF pilot Richard Blaney is suspected of being the "Neck Tie Murderer" — a vicious serial killer terrorising London. With the help of his friends, Blaney goes on the run, determined to prove his innocence.

Production

Arthur La Bern's novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square was published in 1966 and it is believed that Hitchcock read it during the autumn of 1970, whilst looking for a new project after the disappointment of Topaz. He later told journalist Rebecca Morehouse, "The book was sent me by the publisher. I was attracted by the market [scenes] and by the central figure, an Air Force man who is always a loser. Today is the day of the nonhero, isn't it?"[1]

Excited by the possibilities the novel offered, he began preparing ideas, which included repurposing the title "Frenzy" from the previously abandoned Kaleidoscope project.

Unlike some of the other British-based novels that Hitchcock had adapted whilst in Hollywood, such as The Trouble with Harry, he felt this one would be better suited to being filmed in London with an all-British cast.

Pre-Production

In early December, Hitchcock pitched his plans to Lew Wasserman and Edd Henry over a lunchtime meeting and they accepted, with the proviso of a $2.8 million budget. By late December, Henry had acquired the film rights to "Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square" for $25,000.[2]

On New Year's Eve, Hitchcock telephoned British playwright Anthony Shaffer — author of the hit stage play Sleuth that was currently running on Broadway — to request that he adapt La Bern's novel.

Although Shaffer would later say that he thought the phone call was a friend playing a practical joke on him, he had in fact already been sent a copy of the novel and had earlier contacted Hitchcock's office to say he liked the story.[3]

Screenplay

Hitchcock met with Shaffer in New York in early January 1971 to discuss the adaptation. Shaffer then accompanied Hitchcock to London to help scout possible locations around the capital, including Hyde Park, Leicester Square, Piccadilly, Oxford Street, Bayswater, Hammersmith, and Covent Garden Market.[4][5]

Returning to the US, script meetings continued throughout February. As was typical, Hitchcock dined on steak and salad — Shaffer once asked he might have something different: "I shouldn't have. Next day, a fifteen-course dinner arrived, catered by Chasen's, and was laid at my tableside. Hitch, of course, had his small steak and salad."[6]

Several parts of the novel were jettisoned or cut back for the screenplay — La Bern's beloved lengthy court scene was reduced in a typically concise Hitchcockian manner and Blaney's temporary escape to France was removed. The director also insisted on including phrases from his childhood, leading Shaffer to later tell biographer Donald Spoto that "[Hitchcock] was intractable about not modernising the dialogue of the picture, and he kept inserting antique phrases I knew would cause the British public a hearty laugh or even some annoyance."[7]

The downbeat ending of the book — Blaney escapes from prison and breaks into Rusk's flat only to discover the serial killer has fled and left behind the body of Monica Barling — was changed to a more satisfying resolution that brought together Blaney, Rusk and Chief Inspector Oxford for a final showdown.

Hitchcock and Shaffer added a recurring theme of food — often inedible or sullied — along with biblical references to the Garden of Eden and Original Sin. The part of Chief Inspector Oxford was enhanced and important light-relief was added with the domestic meal scenes between Oxford and his wife. In his biography of Hitchcock, Patrick McGilligan speculates that the meal scenes may have been autobiographical — Alma was an extremely talented cook whereas Hitchcock often liked to eat the traditional British food of his childhood.[8]

Frenzy was one of the rare Hitchcock films where only one writer developed the entire screenplay, which was completed well before filming began in July.

Casting

Hitchcock travelled to London in May 1971 to hire a British cast and crew, often choosing to renew old acquaintances: cinematographer Gilbert Taylor had worked as a clapper-boy on Number Seventeen, sound mixer Peter Handford had previously worked with Hitchcock on Under Capricorn, and actress Elsie Randolph had played the ship's busybody in Rich and Strange.

As with Psycho, where Norman Bates is an older man in the novel, Hitchcock again cast a younger actor as the antihero Richard Blaney — a slight name change from the novel's "Richard Blamey", who is aged nearly 50.[9] Although Hitchcock had been keen to cast Michael Caine, he proved unwilling and Hitchcock instead selected Jon Finch. According to Taylor, when Finch later openly critised the script's dialogue to journalists, Hitchcock was so angry that he almost recast the role.[10][11]

For the other roles, Hitchcock cast seasoned British stage and screen actors, including Barry Foster, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, Anna Massey, Billie Whitelaw, Alec McCowen and Vivien Merchant. However, without any high profile stars, this risked limiting the box-office potential of the film.[12] Finding an actress for the role of Monica Barling, Mrs. Blaney's secretary, proved more problematic and Jean Marsh was cast shortly after filming began in late July.

Alma's Stroke

Alma had flown to London with her husband with the intention of spending a few weeks in England before embarking on a tour of Europe with her daughter Patricia and granddaughter Mary. Along with various social events, the Hitchcocks managed to fit in a weekend break to Scotland at the start of June, which may have rekindled their long-held desire to film Mary Rose there.[13]

In the early hours of Wednesday June 9th, Alma suffered a serious stroke. Fortunately her husband's personal physician, Dr. Walter Flieg, was on hand and tended to her immediately. Alma insisted on being treated at Claridge's hotel — where she received round-the-clock care — rather than be admitted to hospital. She soon recovered enough to join her husband in viewing the film dailies and Barry Foster recalled that Alfred awaited her reaction "like a schoolboy, showing his homework to the teacher."[14]

In early October, Alma flew back to Los Angeles, accompanied by her's husband's secretary Sue Gauthier, where she received further treatment at home and awaited the return of her husband, who flew back to the US in late October.[15][16]

Principal Photography

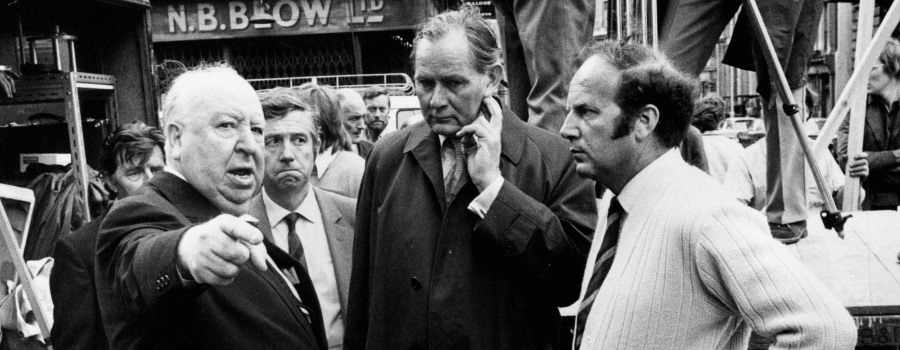

The 13 weeks of filming started in the last week of July 1971, with assistant director Colin M. Brewer heading the second unit. Brewer also handled many of the setups for Hitchcock, who suffered from arthritis that restricted his mobility, and also took over directing on a couple of occasions when Hitchcock was unwell.[17]

Discussing the look he wanted for the film, Hitchcock told cinematographer Gilbert Taylor that he wanted a realistic nightmare, rather than a "Hammer Horror", with the colourful Covent Garden as the backdrop.[18] Hitchcock also used a selection of colour reproductions of Vermeer paintings to illustrate the look he wanted to achieve with the film.[19]

Filming progressed relatively smoothly, although the English weather meant that "weather cover" studio-based scenes at Pinewood Studios, were often on standby in case heavy rain stopped location based shots. Permission to film inside the Old Bailey was granted, but on the proviso that it could only done at a weekend.[20]

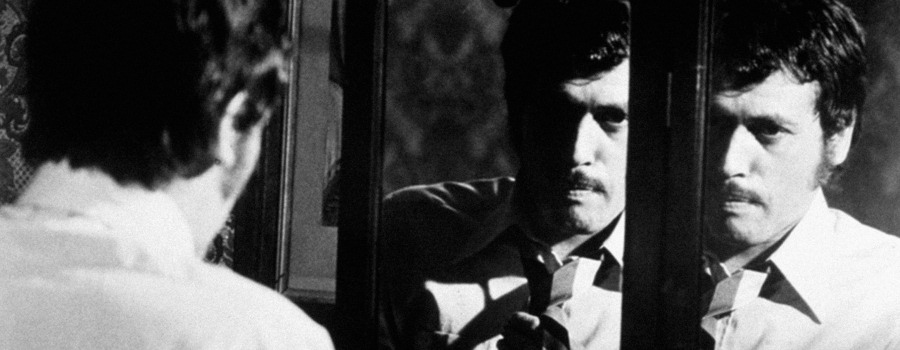

By all accounts, Hitchcock acted coolly towards Jon Finch during filming — partly due to Finch's comments to the press and possibly to unnerve the actor into giving a more nervous performance — insisting that he stick to his character's written dialogue. According to Taylor, several over-the-shoulder shots that would normally have included Finch's back were reframed to exclude the actor. Instead, the camera — and indeed Hitchcock too — seemed to favour the film's villain, Bob Rusk.[21][22] According to Anthony Shaffer, Hitchcock made Finch apologise to the entire cast for the actor's persistently late arrival on set.[23].

The final 3 weeks of filming were mostly taken up with shooting the complex sequence aboard the potato truck and principal photography wrapped on October 14th. Remaining pickup shots, inserts and second-unit work continued for a further week.[24]

Hitchcock flew out of London at 1pm on the October 26th on TWA Flight #761 and his assistant, Peggy Robertson, followed him to Los Angeles with the actual film 2 weeks later. On arriving back in Hollywood, Hitchcock sent the following memo to Universal: "Principal photography has been completed on FRENZY."[25]

Post-Production

Peggy Robertson arrived back in Los Angeles with the film on November 11th. Hitchcock and editor John Jympson spent the rest of the month creating a version of the film that would be suitable for Henry Mancini to time his score. Throughout the editing process, Hitchcock refined the film's soundtrack — the "Final Dubbing Notes" from November 26th ran to 12 pages.

Armed with copious notes from Hitchcock, Jympson flew out to London at the end of November to oversee further edits and post-synching of dialogue, ready for Mancini to record the score in mid-December.

Henry Mancini's Unused Score

Although Henry Mancini is perhaps best-known for his work on films such as Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961) and the Pink Panther series, he began his career writing cues for Universal's 1950s horror and sci-fi films, including The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and It Came from Outer Space (1953). The decade ended with his acclaimed score for Orson Welles's Touch of Evil.

According to Mancini's autobiography, he met with Hitchcock do discuss ideas for the score during the autumn of 1971 — no documents detailing the meeting have survived in the Hitchcock archives held by the Margaret Herrick Library — and it is likely Hitchcock specified which scenes required music.[26] Mancini was sent a copy of the final screenplay at the start of November and had completed the score by early December — for which he was paid a flat fee of $25,000.[27]

Speaking to Catherine Stott of The Guardian, just after the recording sessions, Mancini talked about the score:

You want to know how I go about scaring people? Really it is a matter of colours. Of using the orchestra in various combinations to create tension. "Frenzy" is very low-key picture about a neck-tie murderer, and wha I have done is to just cut off the orchestra round middle C. There is no high — there are no violins nor high flutes — it is all from there down with ten cellos, ten violas, basses, horns, bassoon, and bass flutes ... none of the screeching, high, intense sounds that would be though a little melodramatic today. It is very sparse... there's not a lot going on, but what there is will, I trust, sound pretty spooky.[28]

Hitchcock attended the end of the London recording sessions in mid-December (12th-15th) and then rejected the completed score outright. In his autobiography, Mancini wrote:

It was not so much a matter of his being there as that [Hitchcock] didn't say much when we were doing [the recordings]. He sat through every piece and nodded approval, and finally, when he was alone in the dubbing room, he decided that it didn't work. His reason for thinking so, I was told, was that the score was macabre, which puzzled me because it was a film with many macabre things it in. It wasn't an easy decision to accept, and it was crushing when it happened...[29]

Unlike Hitchcock's acrimonious split with Bernard Herrmann over the rejected score for Torn Curtain, it seems Mancini was not left too bitter by the experience and fondly recalled in his autobiography how Hitchcock had sent him a case of Château Haut-Brion magnums.[30]

The claim that Hitchcock rejected the score during the recording sessions by telling Mancini, "Look, if I want Herrmann, I'd ask for Herrmann!" is apocryphal and was made by Herrmann in a 1975 interview with Royal S. Brown.[31]

The Second Composer: Ron Goodwin

After rejecting the Mancini score, Hitchcock hired British composer Ron Goodwin and provided him with detailed instructions and notes regarding the new score. A in-depth analysis of Mancini's unused score by Gergely Hubai, published in the "Hitchcock Annual" (vol 17), shows that Hitchcock then significantly revised the placement of music within the film — several scenes that were scored by Mancini had no music in the final version of the film.

The London recording sessions for Goodwin's score began on Monday 31st January 1972 and were completed by the end of the week.[32]

By mid-February, Jympson had synced Goodwin's score and the film was shipped back to Los Angeles. Further small edits and soundtrack alternations were then made to fine tune the film, which was deposited in the Universal Studios vault by the end of the month.[33]

Upon seeing the completed film at a studio screening, Norman Lloyd enthusiastically stated that Frenzy was "the picture of a young man."[34]

Release & Reception

Film historian Arthur Knight, a professor of cinema at University of South California, was hired to write the official synopsis of the film for the studio's publicity brochure and wrote to Hitchcock to say: "In all seriousness, I feel that this is your best work ... since North by Northwest." Knight also invited Hitchcock to attend one of his lectures and, on April 27th 1972, Knight's students were treated to an unofficial premiere of Frenzy.[35]

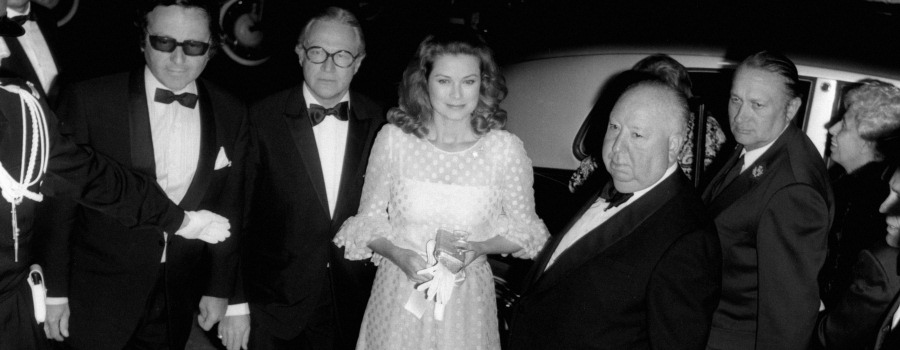

In May 1972, the Hitchcocks sailed to Cannes Film Festival to show Frenzy out of competition — where it was immediately hailed as a late-career masterpiece — before travelling on to Paris for a screening. Truffaut, who had met a stressed and worried Hitchcock at Cannes, said that the director looked "fifteen years younger" in Paris now that he knew he had a critical success on his hands.[36][37]

The London premiere was held on Thursday May 25th.[38] Hitchcock was interviewed that morning on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme and was asked about famous murder cases and what cuts were required in Frenzy to appease the British censor:

In his review for TIME, Jay Cocks' wrote "It is not at the level of his greatest work, but it is smooth and shrewd and dexterous, a reminder that anyone who makes a suspense film is still an apprentice to this old master."[39] and Albert Johnson's review in the Film Quarterly journal called Frenzy "Hitchcock's return to the realm he commanded so long: the fears and excitement felt when viewing and hearing the stories of a diabolical narrator."[40]

Writing in The Guardian, Derek Malcolm was less enthusiastic: "the whole thing amounts to little more than a rather cynical and not very psychologically sound jape constructed out of virtually nothing by a master craftsman with nowhere much to go."[41]

John Russell Taylor's positive review in The Times opened with "The very first scene of Alfred Hitchcock's new film immediately makes one feel at home. This is Hitchcock, and this is Hitchcock's London", before praising Shaffer's script, and ended with Taylor stating Hitchcock was a "great director again making a film worthy of his great talents; the magic remains intact."[42]

Two people who regarded the film less favourably were the French playwright Charles de Peyret-Chappuis, who successfully sued Hitchcock for 150,000 francs for using the title Frenzy — a French court agreed that it was too similar to the title of Peyret-Chappuis' 1938 play Frénésie[43] — and author Arthur La Bern, who expressed his displeasure with the film adaptation of his novel in a letter to the Editor of The Times:

Sir, I wish I could share John Russell Taylor's enthusiasm for Hitchcock's distasteful film, "Frenzy". I endured 116 minutes of it at a press showing and it was, at least to me, a most painful experience [...] The result on the screen is appalling.[44]

The publicity tour for Frenzy lasted well into the year. Crucially for Hitchcock, Alma had recovered sufficiently from her stroke to accompany him on the tour.

At the end of 1972, Variety listed the film at #33 in their "Top 50 Grossing Films of the Year" list, with a total box-office return of $4,809,694. Vincent Canby, film critic for The New York Times, included Frenzy in his top 10 films of the year.[45]

Depiction of Violence

Frenzy contained Hitchcock's most graphic depiction of violence in the rape/murder of Brenda Blaney, which prompted wide ranging discussions on misogyny and violence in both Hitchcock's films and in Hollywood films more broadly.

Although both the US and UK censors required minor cuts to be made to the sequence, it should be noted that Hitchcock and Shaffer had already toned down the level of violence depicted in the source novel, with the second murder mostly implied rather than shown[46][47] — similarly, in Robert Bloch's novel "Psycho", Mary Crane meets a more violent death at the Bates Motel when she is decapitated in the shower.

In her analysis of the film, Tania Modleski notes:

Of course, one might ask why, if a sordid crime like rape/murder is to be depicted at all, it should not be shown "in all its horror." [...] Hitchcock's use of graphic details, his casting of ordinary non-fetishized women in the various female roles, and his refusal to eroticize the proceedings as he had in Psycho [...] all this makes the crime he is depicting more difficult for the spectator to assimilate.[48]

In his book on the making of the film, Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece, Raymond Foery devotes an entire chapter to the issues raised by the film and references a number of key texts, including:

- The New York Times (30/Jul/1972) - Does 'Frenzy' Degrade Women? by Victoria Sullivan

- Screen (1975) - Visual pleasure and narrative cinema by Laura Mulvey

- Can Hitchcock be saved for feminism? by Robin Wood

- Cineaste (1984) - Hitchcock's Women by Susan Jhirad

- Film Quarterly (1985) - The Representation of Violence to Women: Hitchcock's "Frenzy" by Jeanne Thomas Allen

- The Women Who Knew Too Much (2005) by Tania Modleski — chapter on Frenzy

- Literature Film Quarterly (1999) - Hitchcock's women on Hitchcock by Greg Garrett

- Alfred Hitchcock: The Legacy of Victorianism (2006) by Paula Marantz Cohen

See Also...

For further relevant information about this film, see also...

- 1000 Frames of Frenzy (1972)

- articles about Frenzy (1972)

- awards and nominations

- books

- complete cast and crew

- cut scenes

- documentaries

- filming locations

- soundtrack albums

- quotations relating to the film

- trailers

- trivia

- web links to articles, information, reviews, etc

Blu-ray Releases

released in 2012

|

Frenzy (1972) - Universal (Blu-ray, 2012) available as an individual disc or as part of the box set Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection - Universal (Blu-ray, 2012) |

DVD Releases

released in 2006

|

Frenzy (1972) - Universal (USA, 2006) Amazon (USA) NTSC 1.78:1 (anamorphic) |

released in 2005

|

Frenzy (1972) - Universal (UK, 2005) Amazon (UK) PAL |

|

Frenzy (1972) - Universal (USA, 2005) as part of a box set Amazon (USA) NTSC 1.78:1 (anamorphic) [01:55:44] |

Image Gallery

Images from the Hitchcock Gallery (click to view larger versions or search for all relevant images)...

posters

lobby cards

other images

Film Frames

Themes

- the MacGuffin - Bob Rusk's tie pin

- hero falsely accused of being the "Necktie Murderer"

- hero on the run from the police

- taboo: bathrooms - the murderer hides in one after leaving the potato truck

- taboo: nudity - Babs walking across the hotel room

- taboo: sex - the rape and murder of Brenda

- stairs - The tracking shot down the stairs as Babs is being murdered.

- the double - Richard and Bob

- the Hitchcock cameo - in the crowd at the start of the film (more details)

Cast and Crew

Directed by:

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Colin M Brewer - assistant director (2nd unit)

Starring:

- Jon Finch - Richard Blaney

- Alec McCowen - Chief Insp. Oxford

- Barry Foster - Robert Rusk

- Billie Whitelaw - Hetty Porter

- Anna Massey - Babs Milligan

- Barbara Leigh-Hunt - Brenda Blaney

- Bernard Cribbins - Felix Forsythe

- Vivien Merchant - Mrs Oxford

- Michael Bates - Sergeant Spearman

- Jean Marsh - Monica Barling

- Clive Swift - Johnny Porter

- John Boxer - Sir George

- Madge Ryan - Mrs Davison

- George Tovey - Mr Salt

- Elsie Randolph - Gladys

- Jimmy Gardner - Hotel Porter

- Noel Johnson - Doctor in Pub

Produced by:

- Alfred Hitchcock - producer (uncredited)

- William Hill - associate producer

Written by:

- Anthony Shaffer - screenplay

- Arthur La Bern - original novel ("Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square")

Photographed by:

Edited by:

Music by:

Production Design by:

Notes & References

- ↑ Lima News (16/Jul/1972) - Alfred Hitchcock Not a Male Chauvinist

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, pages 10-11

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 13

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, pages 698-9

- ↑ The Times (11/Jan/1971) - Hitchcock to make film in London

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 700

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 701

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, pages 701-2

- ↑ It's highly likely that Hitchcock made the name change to "Blaney" as a symbolic link back to his childhood — when his father moved the family business from Leytonstone to Limehouse, they took over a fishmongery at 175 Salmon Lane previously owned by Benjamin Blayney.

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 704

- ↑ The Times (03/Aug/1971) - Murder with comedy at Covent Garden Market

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 703

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, 708

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 708

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan pages 708-9

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, pages 42, 77 & 99

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, pages 64-5

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, pages 702-3

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 41

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 56

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 704

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, chapter 7

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 65

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 66

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery pages 96 & 103

- ↑ Hitchcock Annual (2011) - "Murder Can Be Fun": The Lost Music of Frenzy - Gergely Hubai

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 106

- ↑ The Guardian (29/Dec/1971) - Henry Mancini

- ↑ Henry Mancini - "Did They Mention the Music?", pages 155-6

- ↑ Wikpedia: Château Haut-Brion

- ↑ An Interview with Bernard Herrmann (August 1975)

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 108

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, pages 108-9

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 109

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 112-3

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (2003) by Patrick McGilligan, page 712

- ↑ The Times (12/Apr/1972) - Films chosen for the Cannes Festival

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, 114

- ↑ TIME (1972) - Still the Master

- ↑ Film Quarterly (1972) - Frenzy

- ↑ The Guardian (25/May/1972) - Strangled laughter

- ↑ The Times (23/May/1972) - Frenzy: Hitchcock magic is intact

- ↑ The Times (16/Mar/1973) - Damages over Hitchcock film

- ↑ The Times (29/May/1972) - Letters to the Editor: Hitchcock's "Frenzy"

- ↑ Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012) by Raymond Foery, page 125

- ↑ The rape/murder originally ended with a close-up of spittle dripping from the dead Brenda Blaney's mouth, but Hitchcock was persuaded this was a step too far and a freeze-frame of Brenda's face was used instead.

- ↑ The Times (03/Jan/1972) - Censor trims Hitchcock film

- ↑ The Women Who Knew Too Much (2005) by Tania Modleski

| Hitchcock's Major Films | |

| 1920s | The Pleasure Garden · The Mountain Eagle · The Lodger · Downhill · Easy Virtue · The Ring · The Farmer's Wife · Champagne · The Manxman · Blackmail |

| 1930s | Juno and the Paycock · Murder! · The Skin Game · Rich and Strange · Number Seventeen · Waltzes from Vienna · The Man Who Knew Too Much · The 39 Steps · Secret Agent · Sabotage · Young and Innocent · The Lady Vanishes · Jamaica Inn |

| 1940s | Rebecca · Foreign Correspondent · Mr and Mrs Smith · Suspicion · Saboteur · Shadow of a Doubt · Lifeboat · Spellbound · Notorious · The Paradine Case · Rope · Under Capricorn |

| 1950s | Stage Fright · Strangers on a Train · I Confess · Dial M for Murder · Rear Window · To Catch a Thief · The Trouble with Harry · The Man Who Knew Too Much · The Wrong Man · Vertigo · North by Northwest |

| 1960s | Psycho · The Birds · Marnie · Torn Curtain · Topaz |

| 1970s | Frenzy · Family Plot |

| view full filmography | |